Abstract

Purpose

Cervical cancer disproportionately burdens low-resource populations where access to quality screening services is limited. A greater understanding of sustainable approaches to implement cervical cancer screening services is needed.

Methods

We conducted a systematized literature review of evaluations from cervical cancer screening programs implemented in resource-limited settings globally that included a formal evaluation and intention of program sustainment over time. We categorized the included studies using the continuum of implementation research framework which categorizes studies progressively from “implementation light” to more implementation intensive.

Results

Fifty-one of 13,330 initially identified papers were reviewed with most study sites in low-resource settings of middle-income countries (94.1%) ,while 9.8% were in low-income countries. Across all studies, visual inspection of the cervix with acetic acid (58.8%) was the most prevalent screening method followed by cytology testing (39.2%). Demand-side (client and community) considerations were reported in 86.3% of the articles, while 68.6% focused scientific inquiry on the supply side (health service). Eighteen articles (35.3%) were categorized as “Informing Scale-up” along the continuum of implementation research.

Conclusions

The number of cervical cancer screening implementation reports is limited globally, especially in low-income countries. The 18 papers we classified as Informing Scale-up provide critical insights for developing programs relevant to implementation outcomes. We recommend that program managers report lessons learnt to build collective implementation knowledge for cervical cancer screening services, globally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, there are over a half million new cases of cervical cancer yearly, with nearly 90% of these cases in least developed economies [1]. The United States (US) 2012 cervical cancer incidence rate was 8.1 per 100,000 women, while low- and middle- income countries (LMICs) had a collective rate of 15.7 [2]. Cervical cancer screening programs detect pre-cancerous lesions which can be treated with low-cost outpatient procedures, and if invasive cancers are caught early, successful treatments exist.

Cervical cancer disproportionately affects populations in resource-limited settings globally despite the variety of evidence-based screening options. Technological innovation and efficacy testing of health service interventions including various screening modalities [3, 4] have led to clear recommendations for improving cancer control among HPV vaccination programs and cervical cancer screening using locally appropriate methods [5,6,7]. Nonetheless, the judicious implementation of evidence-based cervical cancer screening programs remains inadequate, resulting in persistently elevated cervical cancer incidence and mortality rates, especially in resource-limited settings [8].

Gaps in the literature

The 2011 WHO Prioritized Research Agenda for Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Disease notes that while cancer screening services have been shown to be effective in high-income countries (HICs) [9,10,11,12] and HPV screening has been shown to reduce cervical cancer deaths in resource-limited settings such as rural India [13], there are few reports describing the implementation of successful and sustained cervical cancer screening programs in LMICs. Research that examines cervical cancer screening program barriers and facilitators within specific contexts and informs the adaptation of evidence-based interventions within these contexts is needed to ensure the successful implementation and sustainment of programs across various settings [6, 14].

In 2015, a scoping study of existing reviews on breast and cervical cancer in low- and middle- income countries concluded that current cervical cancer literature focuses primarily on prevention and detection, largely without implementation considerations [15]. An additional finding articulated that articles occasionally provide programmatic or policy recommendations that are beyond the context of their own studies’ findings. However, specific recommendations of the implementation methodologies relevant to issues of governance, systems development, workforce capacity, and person/ community centeredness for arriving at these conclusions are often lacking.

Cervical cancer screening

Various evidence-based cervical cancer screening techniques have been developed, tested, and are appropriate for diverse contexts. High-resource settings often employ cytologic screening through Papanicolaou (Pap) smear with follow-up colposcopy and biopsy to identify early-stage dysplasia and pre-cancerous lesions. Cytologic screening can be resource heavy by requiring specialized specimen preservation and advanced technical expertise employing cyto-pathologists. Visual inspection methods can complement other screening modalities and provide adequate sensitivity and specificity to identify later-stage pre-cancers which can then be treated through cryotherapy freezing or loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), curative modalities commonly implemented alongside visual inspection screening services in low-resource settings. In addition, human papillomavirus (HPV) testing has the highest sensitivity for high-grade lesion detection and can be obtained through clinician-sampled or self-sampling techniques. HPV testing can be used for primary screening in conjunction with cytology or visual inspection for triage if the infrastructure exists. Despite the many screening modalities appropriate for a variety of contexts, there remains poor cervical cancer screening coverage, globally. Gakidou et al. reports a coverage rate of 36.9% globally and only 18.5% in least developed countries [16].

Dissemination and implementation science for cancer research and health systems strengthening

This systematized review addresses the following questions: (1) “What published literature has reported implementation evaluations for cervical cancer screening programs in resource-limited settings, particularly those linked to sustainable systems (e.g., governmental) that will have a population-level impact?” and, (2) “What are the reported program implementation-relevant contextual findings applicable to guide the adaptation of cervical cancer screening programs into a wide range of settings to support cervical cancer prevention and control strengthening efforts worldwide?.”

By applying the “Continuum of Implementation Research” framework (see Table 4 for definitions and examples) to papers included within this review, our intent is to highlight how the existing catalog of cervical cancer implementation research conforms to various levels of implementation science rigor. This allows the reader to readily identify papers most relevant to the various stages of implementation. The themes of this continuum are defined as follows: (1) Proof of Concept (Implementation not relevant or relevant, but not considered), (2) Proof of Implementation (Implementation relevant, but effects reduced), and (3) Informing Scale-up (Implementation studied as contributing factors or as primary focus) [17].

Methods

We conducted a systematized literature review [18] of cervical cancer screening program implementation evaluations. Inclusion criteria were that the article (1) states the cervical cancer screening intervention occurred in a resource-limited setting in any country, (2) clearly defines implementation evaluation of the intervention with consideration of any defined implementation-relevant outcomes (acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, feasibility, fidelity, coverage, sustainability) [17], and (3) articulates evidence or intent of the intervention sustainment over time or through policy change by describing or reporting factors relevant to the inner (e.g., organizational characteristics, fidelity monitoring, staffing) or outer context (sociopolitical, funding, public-academic collaboration) [19]. The only exclusion criterion was publication in a language other than English.

Search strategy

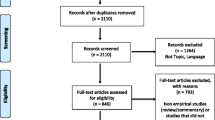

In July 2015, a search of PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science, POPline, and IndMED included all years up to July 2015 in the initial title review and limited the search to publications in peer-reviewed journals. Search terms were based on four themes: cervical cancer screening, low resource, evaluation, and population level. (see additional file #1 for an example PubMed search string).

We used a multi-step process to select the articles for our review. Three independent reviewers conducted an initial screening for the inclusion criteria based on article titles and labeled them: “yes,” “no,” or “maybe.” If any of the reviewers labeled the title as a “yes” or “maybe,” it advanced to the next round of review. Articles identified as having a focus on cervical cancer were further screened to determine whether or not they included an evaluation of a screening intervention. Therefore, as a next step, abstracts and full articles (if needed) were reviewed by two reviewers to assess all inclusion and exclusion criteria. All discrepancies were discussed verbally in weekly meetings, with resolution by agreement between the two reviewers and an additional author. All data were managed through a shared and continually updated database.

Data collection

The lead authors, through mutual agreement, devised and refined the data abstraction tool based, in part, on the Implementation research framework proposed by Peters et al. [17] Abstracted items included the following: location of study, partners, scale of intervention (national, regional, district, etc.), motivation of intervention, intervention description, study methodology, independent variables, screening approach (e.g., VIA, cytology, HPV), health system level of intervention, and identified implementation barriers. The two reviewers then each completed a test round of abstraction of the same 10 manuscripts. These abstracts were then reviewed and compared by one of the authors for discrepancies. The team met again to discuss these discrepancies and resolve any issues. The remaining articles were then abstracted by one of two reviewers. The team met once per week to discuss issues or questions related to abstraction.

Information was abstracted directly from the publication without interpretation for all categories with the following exceptions. To categorize the identified “Partners” (Table 1) and “Demand and Supply Side Implementation Barriers” (Table 2), we standardized the terminology with guidance from Peters [17] and Proctor [20]. To determine this categorization, both explicit information from the article as well as interpretation and commentary by the reviewing authors was considered. This subjective interpretation was necessary given the current lack of universal standardization of implementation science terminology [21]. Peters [17] includes guidance on the grouping of related terms, but it is not exhaustive and did not apply in all cases. Wherever subjective assessment was used, the lead author made a final determination on categorization for consistency. (Supplement 2).

Analysis and summary of findings

All lead authors were provided with the abstraction document and asked to independently assess emerging themes. Based on the abstracted information contained in the fields, motivation of intervention; description of intervention; methodology; variables; implementation barriers; findings; recommendations; and research or practice gaps were identified. We categorized the reviewed studies along a continuum of implementation research [17]. We assigned a single label to each paper among three categories: (1) Proof of Concept (Implementation not relevant or relevant, but not considered); (2) Proof of Implementation (Implementation relevant, but effects reduced); and (3) Informing Scale-up (Implementation studied as contributing factors or as primary focus). (Table 4).

Finally, we categorized barriers identified through the reported implementation research and organized them according to the Patient-Centered Access to Healthcare Framework proposed by Levesque [22]. This Framework specifies barriers on both the demand side (client and community perspective) as well as the supply side (health services level). Within this framework, demand-side barriers are subcategorized into the client’s ability to “Perceive,” “Seek,” “Reach,” “Pay,” and “Engage” with the community health system, while supply-side barriers are subcategorized into the health service’s “Approachability,” “Acceptability,” “Availability and Accommodation,” “Affordability,” and “Appropriateness” on the part of clients [22].

Reporting

Reporting in this analysis refers to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for reporting results of systematic reviews (S1) [23]. (Supplement 2).

Results

Fifty-one of 13,330 initially identified papers met inclusion criteria. Twenty-five (49.0%) of the articles were published between 2011 and 2015 compared to only four (9.8%) being published between 2001 and 2005. When analyzed by the World Bank Income level [24], only five (9.8%) had sites discussed in the papers in low-income countries (three of which were in Uganda), while twenty-six (51.0%) sites were in lower-middle-income countries. (Table 1).

The studies reviewed and tested a variety of screening methods, and many of the studies tested multiple methods. Visual inspection was the most prevalent screening method, including 30 (58.8%) VIA studies and eight (15.7%) studies that considered VILI. Cytology testing was second most common, with 20 (39.2%) associated studies. The scale of intervention was distributed towards smaller-scale interventions. Thirty-three (64.7%) were conducted at the city or district level, while only five (9.8%) were at the national level. Forty-four of the 51 studies clearly described the involvement of multiple partners. Of all 51 studies, 26 (51.0%) indicated involvement of national academic institutions and 19 (37.3%) reported involvement of international institutions. Most engaged health systems including those at the local (n = 34, 66.7%), national (n = 22, 43%), and international (n = 3, 5.9%) levels.

For a more nuanced analysis of the reviewed articles, we categorized the relevance to various levels of implementation. (Table 2) We identified 40 (78.4%) articles pertinent to patient- or client-level considerations. Only 13 (25.5%) are applicable to the quality of clinical services. Twenty-five (49.0%) articles discussed additional health system-relevant themes (financing, information systems, equipment/resources management, leadership/governance, and others).

In addition to identifying the implementation access level of relevance, we, as well, sought to understand the explicit findings regarding barriers identified through the implementation research. Many of the papers reported specific findings relevant to demand-side (n = 26, 51.0%) or supply-side (n = 28, 49%) barriers to the successful implementation of cervical cancer screening services. From the articles presenting demand-side barriers (Table 3), those most often reported include comfort (n = 6, 23.1%), lack of knowledge (5, 19.2%), embarrassment associated with the clinical procedure (n = 3, 11.5%), and patient cost considerations (n = 3, 11.5%). Others receiving fewer mentions include distance to clinic, lack of patient priority for prevention, permission required by husband for procedure, and concern about no sexual intercourse after the procedure.

Of the 28 papers reporting supply-side barriers (Table 3), 22 (78.6%) discuss provider-relevant themes and 16 (57.1%) discuss other health system-relevant considerations. Of the 22 reporting provider-associated barriers, 10 (45.5%) report a lack of opportunity or time to participate in trainings, nine (41.0%) report significant provider turnover as a major barrier, and 6 (27.3%) describe technical deficiencies of the provider as limitation to the impact of the screening program. Of the 16 reporting other system barriers, nine (56.3%) report cost as a major limiting factor in implementation.

As described in the background, we sought to characterize studies along the continuum of implementation research categories. (Table 4) In doing so, we illustrate the value of findings elucidated through studies with well-formulated implementation science questions. Twenty papers (39.2%) were labeled as Proof of Concept, 13 (25.4%) as Proof of Implementation, and 18 (35.3%) as Informing Scale-up. Table 5 details the publications categorized as informing scale-up, stratified by year.

Discussion

The number of articles (n = 51) evaluating the implementation of cervical cancer screening programs in limited resource settings is relatively small compared to the total number of articles identified through the review. Of note, we identified only five papers in low-income countries where settings are likely to have the greatest barriers to building sustainable capacity for cervical cancer screening and where, arguably, there is the most to be learned in vastly improving systems and approaches for screening. Of our reviewed articles, the majority (52.9%) were published between 2011 and 2015, suggesting an upward trend of reporting with the later time of publication. The reporting of experiences and sharing of best practices will contribute to our collective ability to overcome the many challenges in ensuring ultimate sustainability of these programs [76, 77].

The identified studies cover a range of cervical cancer screening methodologies with VIA being the most utilized and studied in our included papers. In addition, 46 (90.2%) papers describe research in decentralized settings with the majority of these (33 of 46, 71.7%) at the district or city level. As well, given the significant shortage of healthcare workforce globally [78], especially in resource-limited settings, it is not surprising that the overwhelming number of supply-side focused studies (32 of 37, 86.5%) considered capacity building. These findings may reflect a trend to integrate an effective, low-resource appropriate technology into existing health services in response to inequities in women’s health care and to strengthen primary health care in decentralized community health systems. The 2008 call [79] to offer more comprehensive packages of basic health services (including improved preventive care services) in all settings and more recent calls [12] to address non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are also consistent with this trend.

These findings provide some insight into the cervical cancer screening implementation literature. We note that articles commonly describe community- and client-relevant implications and explore challenges to human resources. Of interest, however, our analysis reveals that a relatively small percentage of papers describe or report quality assurance themes (25.5%) and a very low percentage (3.9%) describe quality improvement activities related to the implemented health service. Given that only 23.5% of all papers are describing “policy” in explicit terms, the present findings also illustrate a major gap in the literature regarding policy development around the long-term sustainment of cervical cancer screening programs.

Demand-side barriers are identified in 51% of reviewed articles with the most frequent focus on comfort, knowledge gaps, personal sensitivity, and cost. Provider issues (78.6%) make up most supply-side barriers. Much can also be learned from implementation evaluations describing other systems-level issues. The present analysis highlights other explicit concerns including cost, equipment, management practices, space, supervision, and infrastructure.

“Proof of Concept” papers describe studies where implementation is not relevant, or implementation is relevant but not considered as research questions. The context of these studies is focused and the factors affecting implementation are not relevant, fixed, or ignored. Because 20 studies fell into the “Proof of Concept” category and 13 in the “Proof of Implementation,” one could conclude that many of the published articles investigating cervical cancer screening programs are not implicitly structured to provide meaningful information of the real world context in which the research project occurs.

For example, a study in Western Kenya aimed to validate VILI as a stand-alone screening test at a Family AIDS Care and Education Services (FACES) clinic [72] while a study in Leon, Nicaragua compared the acceptability of self-collected versus clinician-collected human papillomavirus (HPV) tests which applies to the “proof of implementation” category [73].

“Proof of Concept” studies may be strengthened by examining more contextual factors to determine screening feasibility in similar settings. Implementation research also has the potential to describe in greater detail the supporting and hindering factors to wide-scale implementation and sustainment of a cervical cancer screening program within the context of their health system’s existing cancer control and prevention policy.

We classified 18 papers as “informing scale-up.” These papers provide useful guidance for developing cervical cancer implementation programs across different contexts. Principally, those contexts include in-depth perspectives on acceptability and community perceptions [53], community education and mobilization [30, 59] including radio messaging [41], community-focused or mobile screening [30, 58], detail on training community health workers [50], client tracking [59], maintenance of human capacity [59], task sharing [65], and quality control [70]. These findings are accessible and highly applicable to the existing programs struggling with substantial challenges as well as to institutions that are prioritizing the new implementation of cervical cancer screening services.A large study in 130 rural communities in Guangdong Province, China [69] employs sound Dissemination and Implementation research methods. Study results described community participatory research through the Chinese Cancer Prevention Study (CHICAPS). This program was conducted by community leaders with the technical assistance of the research team. They utilized a “pass the message on” model to easily reach women in communities through local village promoters that were trained through locally organized workshops (with up to 25 community leaders being oriented). Their paper describes the model process in depth, including details of stakeholder roles. Conclusions were that the model was successful in (1) improving the efficiency of resource utilization, (2) teaching community leaders and promoters to get patient information and follow procedures, and (3) teaching rural women technical specifics of the screening approach.

A three-phase evaluation of a cervical cancer screening program was conducted in the Harare city health department, Zimbabwe [34]. This study included a survey of policy makers on guidelines, policy, and attitudes regarding cervical cancer screening, and evaluating determinants at both the supply- and the demand side. Dissemination of their work provides invaluable guidance on how comprehensive policies on cervical cancer screening should be developed to assist in standardization of program implementation, how the formal technical training of health workers should be done, and what necessary resources should be allocated to support a successful and sustainable cervical cancer screening program.

Finally, a cervical cancer screening evaluation was conducted in Guyana to explore the feasibility, effectiveness, and lessons learned of a single-visit approach to cervical cancer screening and treatment [65]. The reported findings were highly relevant to sustainability and scale-up and concluded that certain components are essential to achieve good population coverage with high-quality services: (i) competency-based training and supportive supervision; (ii) task shifting to non-physician providers; (iii) a strong monitoring and evaluation system that rapidly identifies and addresses programmatic and clinical gaps; (iv) an enabling environment providing programmatic support; and (v) integration of cervical cancer prevention services into appropriate existing programs, such as family planning, postpartum, and HIV care.

Limitations

Due to limitations in our search strategy and a lack of a risk of bias assessment, our review is characterized as a systematized review [18]. Given that our search strings were composed entirely of Medical Subject Heading (MESH) terms, we relied primarily on the accurate and current MESH terms and did not pursue the addition of articles through a free text search. Given the time limitations, MESH terms were used only to reduce the time associated with the search strategy development. This is problematic given that much of the published research from LMICs is not likely to be well indexed. Searches may therefore have left out relevant articles. Additionally, our search was conducted in the July of 2015. Any articles that were published after the search were not included in the review, omitting articles that would have met the criteria. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were strict for this literature review. Many articles were excluded from this review that provide valuable lessons in a variety of settings outside of the scope of our inclusion criteria, but were not regarded as employing implementation science. The findings from these excluded papers nevertheless may contain some findings relevant to implementation science and could be generalizable or be adaptable in areas with low resources. Additionally, it should be noted that the Continuum of Implementation Research as proposed by Peters [17] has limitations with a degree of subjectivity and author interpretation as described in the methods section. Every effort was made to consult the guiding framework and limit subjectivity by systematically and uniformly categorizing articles. Finally, the risk of bias for the included papers was not assessed.

Conclusions

Many evidence-based health service interventions are not being readily adopted in LMICs because of an insufficient primary health care system in place to support them [79,80,81]. More Dissemination and Implementation research is needed to illustrate how health systems function at the local level, especially in LMICs [17]. Much of the existing Dissemination and Implementation science exploring the interface between health research and policy is concentrated in high-income countries. The paucity of similar research in LMICs presents a major challenge for implementation of preventive measures in these countries [82]. Given that cervical cancer can serve as a proxy for larger health systems issues, more detailed exploration of the barriers and best practices for increasing initial screening uptake and sustaining screening services over time may provide important insights to addressing other persisting women’s health issues and beyond, including the strengthening of broad primary health care services in low-resource settings. For programs wishing to move towards expanding the focus on their inquiry into this area, the two principal references that we have used to analyze the papers in this review are excellent resources for investigators new to implementation science [17, 22].

Given the overwhelming supporting evidence for the effectiveness of various screening technologies, it is unsettling that high cervical cancer incidence rates persist globally. There are clear downward trends of age-standardized incidence (ASI) rates in HIC, although no clear changes by period in low-income countries [83]. Given that a successful cervical cancer control and prevention program requires a robust systems approach including reliable access to primary healthcare, referral, and follow-up services, the incidence of cervical cancer has been shown to be an indicator for larger health systems issues [8]. Therefore, the implementation of cervical cancer prevention and control programs in areas with the least resources would have the greatest immediate impact on cervical cancer ASI rates while potentially favorably impacting other primary health care services. Unfortunately, there is a gradient between reviewed studies conducted in low-income countries (5, 9.8%) and LMICs (29, 56.9%), (Fig. 1). This disparity may be due to the profound difficulty of implementing cervical cancer programs and conducting research in states that are unstable or where infrastructure is significantly lacking. The implementation challenges in these settings may be the greatest to overcome in order to achieve sustainability of impactful interventions. These settings, unfortunately, may also possess the greatest challenges in conducting sound science, contributing to this well-documented research gap [84]. The areas with the greatest need for developing a clear understanding of implementation are, therefore, the most neglected. The dramatic lack of research from lower-resource environments to inform practice, in part, contributes to the continued gap in outcomes in such settings. However, these challenges could be opportunities for impact as well as for building knowledge. Replicating best practices from the most challenging contexts will likely lead to the greatest impact from dissemination of such scientific pursuits.

Program managers will benefit from working closely with researchers to report lessons learnt from programs implementing cervical cancer screening services. Furthermore, we urge researchers to move beyond technological innovation as the primary scientific pursuit and incorporate, when possible, implementation strategies to overcome barriers to health systems integration and sustainability. Researchers should evaluate the implementation of cervical cancer screening programs. This will build the science and practice of how to strengthen human resources capacity, develop responsive policy, and ensure sustained utilization of cervical cancer health services in different geographical settings.

Data availability

All materials, data, code, and associated protocols will be promptly available to readers without qualifications or restrictions. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ASI:

-

Age-standardized incidence

- CHICAPS:

-

Chinese Cancer Prevention Study

- D&I:

-

Dissemination and implementation

- FACES:

-

Family AIDS Care and Education Services

- HICs:

-

High-income countries

- HPV:

-

Human papillomavirus

- LEEP:

-

Loop electrosurgical excision procedure

- LMICs:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- MESH:

-

Medical subject heading

- NCDs:

-

Non-communicable diseases

- NGO:

-

Non-governmental organization

- PERCAPS:

-

Peru Cervical Cancer Screening Study

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines

- VIA:

-

Visual inspection with acetic acid

- VILI:

-

Visual inspection with Lugol's iodine

References

Torre LA, Freddie B, Siegel RL, Jacques F, Joannie L-T, Ahmedin J (2015) Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 65:87–108. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21262

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M et al (2015) Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 136:E359–E386. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.29210

Beasley JW, Starfield B, van Weel C, Rosser WW, Haq CL (2007) Global health and primary care research. J Am Board Fam Med 20:518–526. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2007.06.070172

Gonzalez-Block MA (2004) Health policy and systems research agendas in developing countries. Health Res Policy Syst 2:6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-2-6

Brown ML, Goldie SJ, Draisma G, Harford J, Lipscomb J (2011) Health service interventions for cancer control in developing countries. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, et al. (eds) Disease control priorities in developing countries. World Bank, Washington (DC)

World Health Organization (2007) Cancer control: knowledge into action: WHO guide for effective programmes. WHO. https://books.google.com/books/about/Cancer_Control.html?hl=&id=GL8lAQAAMAAJ

World Health Organization (2010) Package of essential noncommunicable (PEN) disease interventions for primary health care in low-resource settings. World Health Organization, Geneva

Freeman HP, Wingrove BK (2005) Excess cervical cancer mortality: a marker for low access to health care in poor communities. National Cancer Institute, Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities, Bethesda

Vainio H, Bianchini F (2002) Breast cancer screening, IARC handbooks of cancer prevention. IARC, Lyon, pp 157–170

The Cochrane Collaboration (1996) Screening for colorectal cancer using the faecal occult blood test, Hemoccult. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Wiley, Chichester

IARC Handbooks on Cancer Prevention (2005) Volume 10 Cervix cancer screening. IARC, Lyon

Alwan MS (ed) (2011) Prioritized research agenda for prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. World Health Organization, Geneva

Sankaranarayanan R, Nene BM, Shastri SS, Jayant K, Muwonge R, Budukh AM et al (2009) HPV screening for cervical cancer in rural India. N Engl J Med 360:1385–1394

World Health Organization (2015) Comprehensive cervical cancer control: a guide to essential practice. World Health Organization, Geneva

Demment MM, Peters K, Dykens JA, Dozier A, Nawaz H, McIntosh S et al (2015) Developing the evidence base to inform best practice: a scoping study of breast and cervical cancer reviews in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS ONE 10:e0134618. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0134618

Gakidou E, Nordhagen S, Obermeyer Z (2008) Coverage of cervical cancer screening in 57 countries: low average levels and large inequalities. PLoS Med 5:e132. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0050132

Peters DH, Tran NT, Adam T, World Health Organization (2013) Implementation research in health: a practical guide. World Health Organization, Geneva

Grant MJ, Booth A (2009) A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J 26:91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM (2011) Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Adm Policy Ment Health 38:4–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A et al (2011) Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health 38:65–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7

Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK (2017) Dissemination and implementation research in health: translating science to practice. Oxford University Press, New York

Levesque J-F, Harris MF, Russell G (2013) Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health 12:18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-12-18

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 151:264–269. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

World Bank Country and Lending Groups – World Bank Data Help Desk (2018). https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519. Accessed on 4 May 2018]

Hirst S, Mitchell H, Medley G (1990) An evaluation of a campaign to increase cervical cancer screening in rural Victoria. Community Health Stud 14:263–268

Swaddiwudhipong W, Chaovakiratipong C, Nguntra P, Mahasakpan P, Lerdlukanavonge P, Koonchote S (1995) Effect of a mobile unit on changes in knowledge and use of cervical cancer screening among rural Thai women. Int J Epidemiol 24:493–498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-009-0200-1

Pengsaa P, Vatanasapt V, Sriamporn S, Sanchaisuriya P, Schelp FP, Noda S et al (1997) A self-administered device for cervical cancer screening in northeast Thailand. Acta Cytol 41:749–754

Wesley R, Sankaranarayanan R, Mathew B, Chandralekha B, Aysha Beegum A, Amma NS et al (1997) Evaluation of visual inspection as a screening test for cervical cancer. Br J Cancer 75:436–440

Hernández-Avila M, Lazcano-Ponce EC, Ruíz PA, Romieu I (1998) Evaluation of the cervical cancer screening programme in Mexico: a population-based case-control study. Int J Epidemiol IEA 27:370–376

Swaddiwudhipong W, Chaovakiratipong C, Nguntra P, Mahasakpan P, Tatip Y, Boonmak C (1999) A mobile unit: an effective service for cervical cancer screening among rural Thai women. Int J Epidemiol 28:35–39

Kuhn L, Denny L, Pollack A, Lorincz A, Richart RM, Wright TC (2000) Human papillomavirus DNA testing for cervical cancer screening in low-resource settings. J Natl Cancer Inst 92:818–825

Agarwal SS, Murthy NS, Sharma S, Sharma KC, Das DK (1995) Evaluation of a hospital based cytology screening programme for reduction in life time risk of cervical cancer. Neoplasma 42:93–96

Mati JK, Mbugua S, Wanderi P (1994) Cervical cancer in Kenya: prospects for early detection at primary level. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 47:261–267

Moyo IM, Koni NP, Makunike B, Hipshman J, Makaure HK, Gumbo N (1997) Evaluation of cervical cancer screening programme in the Harare City Health Department Zimbabwe. Cent Afr J Med 43:223–225

Nene BM, Jayant K, Malvi SG, Dale PS, Deshpande R (1994) Experience in screening for cervical cancer in rural areas of Barsi Tehsil (Maharashtra). Indian J Cancer 31:34–40

Cronjé HS, Parham GP, Cooreman BF, Beer A, Divall P, Bam RH (2003) A comparison of four screening methods for cervical neoplasia in a developing country. Am J Obstet Gynecol 188:395–400

Sanchaisuriya P, Pengsaa P, Sriamporn S, Schelp FP, Kritpetcharat O, Suwanrungruang K et al (2004) Experience with a self-administered device for cervical cancer screening by Thai women with different educational backgrounds. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 5:144–150

Howe SL, Vargas DE, Granada D, Smith JK (2005) Cervical cancer prevention in remote rural Nicaragua: a program evaluation. Gynecol Oncol 99:S232–S235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.07.094

Doh TAS, Nkele NN, Achu P, Essimbi F, Essame O, Nkegoum B (2005) Visual inspection with acetic acid and cytology as screening methods for cervical lesions in Cameroon. Int J Gynecol Obstet 89:167–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.12.040

Holanda F Jr, Castelo A, Veras TMCW, de Almeida FML, Lins MZ, Dores GB (2006) Primary screening for cervical cancer through self sampling. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 95:179–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.07.012

Perkins RB, Langrish S, Stern LJ, Simon CJ (2007) A community-based education program about cervical cancer improves knowledge and screening behavior in Honduran women. Rev Panam Salud Publica 22:187–193

Palanuwong B (2007) Alternative cervical cancer prevention in low-resource settings: experiences of visual inspection by acetic acid with single-visit approach in the first five provinces of Thailand. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 47:54–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-828X.2006.00680.x

Blumenthal PD, Gaffikin L, Deganus S, Lewis R, Emerson M, Adadevoh S et al (2007) Cervical cancer prevention: safety, acceptability, and feasibility of a single-visit approach in Accra, Ghana. Am J Obstet Gynecol 196:407–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2006.12.031discussion 407.e8–9

Bhatla N, Mukhopadhyay A, Kriplani A, Pandey RM, Gravitt PE, Shah KV et al (2007) Evaluation of adjunctive tests for cervical cancer screening in low resource settings. Indian J Cancer 44:51–55. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-509x.35811

Qiao Y-L, Sellors JW, Eder PS, Bao Y-P, Lim JM, Zhao F-H et al (2008) A new HPV-DNA test for cervical-cancer screening in developing regions: a cross-sectional study of clinical accuracy in rural China. Lancet Oncol 9:929–936. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70210-9

Chumworathayi B, Srisupundit S, Lumbiganon P, Limpaphayom KK (2008) One-year follow-up of single-visit approach to cervical cancer prevention based on visual inspection with acetic acid wash and immediate cryotherapy in rural Thailand. Int J Gynecol Cancer 18:736–742. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01112.x

Bhatla N, Gulati A, Mathur SR, Rani S, Anand K, Muwonge R et al (2009) Evaluation of cervical screening in rural North India. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 105:145–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.12.010

Qureshi S, Das V, Zahra F (2010) Evaluation of visual inspection with acetic acid and Lugol’s iodine as cervical cancer screening tools in a low-resource setting. Trop Doct 40:9–12. https://doi.org/10.1258/td.2009.090085

Zhang Y-Z, Ma J-F, Zhao F-H, Xiang X-E, Ma Z-H, Shi Y-T et al (2010) Three-year follow-up results of visual inspection with acetic acid/Lugol’s iodine (VIA/VILI) used as an alternative screening method for cervical cancer in rural areas. Chin J Cancer 29:4–8

Nuño T, Martinez ME, Harris R, García F (2010) A Promotora-administered group education intervention to promote breast and cervical cancer screening in a rural community along the U.S.–Mexico border: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer Causes Control 22:367–374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-010-9705-4

Hasanzadeh M, Esmaeili H, Tabaee S, Samadi F (2011) Evaluation of visual inspection with acetic acid as a feasible screening test for cervical neoplasia. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 37:1802–1806. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01614.x

Longatto-Filho A, Naud P, Derchain SF, Roteli-Martins C, Tatti S, Hammes LS et al (2012) Performance characteristics of Pap test, VIA, VILI, HR-HPV testing, cervicography, and colposcopy in diagnosis of significant cervical pathology. Virchows Arch 460:577–585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-012-1242-y

Audet CM, Silva Matos C, Blevins M, Cardoso A, Moon TD, Sidat M (2012) Acceptability of cervical cancer screening in rural Mozambique. Health Educ Res 27:544–551. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cys008

Li R, Lewkowitz AK, Zhao F-H, Zhou Q, Hu S-Y, Qiu H et al (2012) Analysis of the effectiveness of visual inspection with acetic acid/Lugol’s iodine in one-time and annual follow-up screening in rural China. Arch Gynecol Obstet 285:1627–1632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-011-2203-4

Nuranna L, Aziz MF, Cornain S, Purwoto G, Purbadi S, Budiningsih S et al (2012) Cervical cancer prevention program in Jakarta, Indonesia: see and Treat model in developing country. J Gynecol Oncol 23:147–152. https://doi.org/10.3802/jgo.2012.23.3.147

Sanad AS, Ibrahim EM, Gomaa W (2014) Evaluation of cervical biopsies guided by visual inspection with acetic acid. J Low Genit Tract Dis 18:21–25. https://doi.org/10.1097/LGT.0b013e31828ce581

Li R, Zhou Q, Li M, Tong S-M, He M, Qiu H et al (2013) Evaluation of visual inspection as the primary screening method in a four-year cervical (pre-) cancer screening program in rural China. Trop Doct 43:96–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049475513495615

Trope LA, Chumworathayi B, Blumenthal PD (2013) Feasibility of community-based careHPV for cervical cancer prevention in rural Thailand. J Low Genit Tract Dis 17:315–319. https://doi.org/10.1097/LGT.0b013e31826b7b70

Paul P, Winkler JL, Bartolini RM, Penny ME, Huong TT, Nga LT et al (2013) Screen-and-treat approach to cervical cancer prevention using visual inspection with acetic acid and cryotherapy: experiences, perceptions, and beliefs from demonstration projects in Peru, Uganda, and Vietnam. Oncologist 18(Suppl):1278–1284. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0253

Satyanarayana L, Asthana S, Bhambani S, Sodhani P, Gupta S (2014) A comparative study of cervical cancer screening methods in a rural community setting of North India. Indian J Cancer 51:124–128. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-509X.138172

Jeronimo J, Bansil P, Lim J, Peck R, Paul P, Amador JJ et al (2014) A multicountry evaluation of careHPV testing, visual inspection with acetic acid, and papanicolaou testing for the detection of cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 24:576–585. https://doi.org/10.1097/IGC.0000000000000084

Bansil P, Wittet S, Lim JL, Winkler JL, Paul P, Jeronimo J (2014) Acceptability of self-collection sampling for HPV-DNA testing in low-resource settings: a mixed methods approach. BMC Public Health 14:596. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-596

Fong J, Gyaneshwar R, Lin S, Morrell S, Taylor R, Brassil A et al (2014) Cervical screening using visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) and treatment with cryotherapy in Fiji. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 15:10757–10762

Guo J, Cremer M, Maza M, Alfaro K, Felix JC (2014) Evaluation of a low-cost liquid-based Pap test in rural El Salvador: a split-sample study. J Low Genit Tract Dis 18:151–155. https://doi.org/10.1097/LGT.0b013e31829aa052

Martin CE, Tergas AI, Wysong M (2014) Evaluation of a single-visit approach to cervical cancer screening and treatment in Guyana: feasibility, effectiveness and lessons learned. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 40(6):1707–1716

Nessa A, Roy JS, Chowdhury MA, Khanam Q, Afroz R, Wistrand C et al (2014) Evaluation of the accuracy in detecting cervical lesions by nurses versus doctors using a stationary colposcope and Gynocular in a low-resource setting. BMJ Open 4:e005313. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005313

Kamal EM, El Sayed GA, El Behery MM, El Shennawy GA (2014) HPV detection in a self-collected vaginal swab combined with VIA for cervical cancer screening with correlation to histologically confirmed CIN. Arch Gynecol Obstet 290:1207–1213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-014-3321-6

Khozaim K, Orang’o E, Christoffersen-Deb A, Itsura P, Oguda J, Muliro H et al (2014) Successes and challenges of establishing a cervical cancer screening and treatment program in western Kenya. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 124:12–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.06.035

Belinson JL, Wang G, Qu X, Du H, Shen J, Xu J et al (2014) The development and evaluation of a community based model for cervical cancer screening based on self-sampling. Gynecol Oncol 132:636–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.01.006

Abuelo CE, Levinson KL, Salmeron J, Sologuren CV, Fernandez MJV, Belinson JL (2014) The Peru Cervical Cancer Screening Study (PERCAPS): the design and implementation of a mother/daughter screen, treat, and vaccinate program in the Peruvian jungle. J Community Health 39:409–415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-013-9786-6

Rosenbaum AJ, Gage JC, Alfaro KM, Ditzian LR, Maza M, Scarinci IC et al (2014) Acceptability of self-collected versus provider-collected sampling for HPV DNA testing among women in rural El Salvador. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 126:156–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.02.026

Huchko MJ, Sneden J, Zakaras JM, Smith-McCune K, Sawaya G, Maloba M et al (2015) A randomized trial comparing the diagnostic accuracy of visual inspection with acetic acid to Visual Inspection with Lugol’s Iodine for cervical cancer screening in HIV-infected women. PLoS ONE 10:e0118568. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118568

Quincy BL, Turbow DJ, Dabinett LN (2012) Acceptability of self-collected human papillomavirus specimens as a primary screen for cervical cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol 32:87–91. https://doi.org/10.3109/01443615.2011.625456

Vet J, Kooijman JL, Henderson FC, Aziz FM, Purwoto G, Susanto H et al (2012) Single-visit approach of cervical cancer screening: see and treat in Indonesia. Br J Cancer 107:772–777. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.334

Sanad AS, Kamel HH, Hasan MM (2014) Prevalence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) in patients attending Minia Maternity University Hospital. Arch Gynecol Obstet 289:1211–1217

Maseko FC, Chirwa ML, Muula AS (2015) Health systems challenges in cervical cancer prevention program in Malawi. Glob Health Action 8:8. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v8.26282

Chary AN, Rohloff PJ (2014) Major challenges to scale up of visual inspection-based cervical cancer prevention programs: the experience of Guatemalan NGOs. Global Health Sci Pract 2:307–317. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-14-00073

Campbell J, Dussault G, Buchan J, Pozo-Martin F, Guerra Arias M, Leone C et al (2013) A universal truth: no health without a workforce. Global Health Workforce Alliance, Geneva

Lerberghe W, Evans T, Rasanathan K, Mechbal A, Lerberghe W, World Health Organization (2008) The World Health Report 2008: primary health care: now more than ever. World Health Organization, Geneva

Ackerly DC, Udayakumar K, Taber R, Merson MH, Dzau VJ (2011) Perspective: global medicine: opportunities and challenges for academic health science systems. Acad Med 86:1093–1099. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318226b455

Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, Reddy KS, Rodriguez MH, Sewankambo NK et al (2009) Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet 373:1993–1995. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60332-9

Hyder AA, Bloom G, Leach M, Syed SB, Peters DH (2007) Future health systems: innovations for equity. Exploring health systems research and its influence on policy processes in low income countries. BMC Public Health 7:309. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-7-309

Vaccarella S, Lortet-Tieulent J, Plummer M, Franceschi S, Bray F (2013) Worldwide trends in cervical cancer incidence: impact of screening against changes in disease risk factors. Eur J Cancer 49:3262–3273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2013.04.024

Commission on Health Research for Development (1990) Health research: essential link to equity in development. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Medical Librarian, Linda Hassman, of Miner Library at the University of Rochester Medical Center for her valuable work in assisting us in developing and implementing our search strategy.

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Prevention Research Centers Program (Cooperative agreements: 1U48DP005026-01S1, 1U48DP005010-01S1, and 1U48DP005023-01S1). The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This review falls under the scope of work for the US. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) funded Global and Territorial Health Research Network through the Prevention Research Centers Program, with the goal to translate chronic disease prevention research into practice. In addition to several partnering institutions, the Global Network Steering Committee consists of two CDC representatives who participated in the study design and review of the manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of data analysis. The corresponding author had final responsibility to submit the report for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study (AD, JSS, MMD, EM, TS, TD) or to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data (AD, MMD, EM, KP, TI, SM, AS, TS), and drafted the manuscript (AD, JSS, MMD, EM, TS) or revised it critically for content (AD, JSS, MMD, EM, TS, KP, TI, SM, AS, TD). All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dykens, J.A., Smith, J.S., Demment, M. et al. Evaluating the implementation of cervical cancer screening programs in low-resource settings globally: a systematized review. Cancer Causes Control 31, 417–429 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-020-01290-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-020-01290-4