Abstract

Contrary to the visible Latinx population growth in rural America, rural Latinx households have experienced far greater economic disparities compared to Whites. Family economic stress predicts parents’ emotional distress, lower family functioning, and places children at high risk for behavior problems. However, few studies have examined the combined effects of economic and acculturative stress on rural Latinx child behaviors, nor the family stress process among rural Latinx immigrant families in the Midwest, a new settlement area for Latinx and other immigrants (Kandel & Cromartie, 2004). Guided by the family stress model (FSM), we examined the relationships among economic pressure, parent acculturative stress, maternal depressive symptoms, parenting competence and child internalizing and externalizing behaviors using a sample of 148 rural low-income Latinx immigrant mothers in a Midwestern state. Structural equation modeling was performed to test these relationships. Results revealed that higher levels of economic pressure and parent acculturative stress were related to higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms, which in turn were associated with lower parenting competence and eventually linking to higher levels of child externalizing behaviors. Maternal depressive symptoms were positively associated with child internalizing behaviors. Parent acculturative stress was also found to be directly linked to child internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Intervention programs that aim to promote health and well-being among rural Latinx immigrant mothers and their children may find it beneficial to incorporate information and strategies that lessen parent acculturative stress and depression, promote parenting competence, and connect families to resources to help reduce economic pressure.

Similar content being viewed by others

In recent decades many U.S. rural Midwestern communities experienced an influx of immigrants and increased racial and ethnic diversity as immigrant families sought affordable living, personal safety, employment and closer proximity to families and friends who previously immigrated to the US (May et al., 2015). Latinx families have outpaced Black families to become the largest segment of the rural minority population (9%, 8%, respectively) (Economic Research Service, 2018), which almost doubled since 2000 (5.5%) (Kandel & Cromartie, 2004). The visible growth of the Latinx population is present in many different regions across rural America, and most significantly in the South and Midwest (Kandel & Cromartie, 2004; May et al., 2015). Despite the significant population growth, economic disparities persist among rural Latinx families. For example, Latinx households experienced far greater poverty rates compared to White households (21.7% and 13.3% in 2019, respectively; U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, 2021). Such economic disparities have been exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic as rural unemployment increased, and serious financial difficulties and large numbers of COVID-19 cases appeared among the Latinx population (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2020). However, compared to traditional Latinx settlement areas of the Southwest, new destinations in rural Midwestern communities where the population has long been dominated by the non-Latinx White communities of western European descent remain economically and culturally ill-prepared to meet the needs of the growing Latinx population (Kandel & Cromartie, 2004; Raffaelli & Wiley, 2012). Thus, the Latinx immigrant population commonly experiences multiple stressors simultaneously, such as ecomonic pressure and acculturative stress (Raffaelli & Wiley, 2012). Economic pressure is an individual’s awareness of and responses to adverse economic circumstances, such as inability to pay bills, cutting back on necessary expenses (Conger et al., 1993). Acculturative stress is an individual’s stress reaction to acculturation – a process of cultural involvement that includes the retainment of culture-of-origin involvement and the establishment of host culture involvement (Berry, 1980; Smokowski & Bacallao, 2006). Stress manifested from economic disadvantage or acculturation has been associated with psychological distress (D’Anna-Hernandez et al., 2015), family dysfunction (Caetano et al., 2007), and adverse Latinx child outcomes (Martinez, 2006). However, little is known about the combined impacts of perceived economic pressure and acculturative stress among Latinx immigrant parents on child behavior problems, as well as the family stress process among low-income Latinx immigrant families residing in rural Midwestern communities.

This study aims to bridge the aforementioned gap by examining (1) the impact of economic pressure and parent acculturative stress on child internalizing and externalizing behaviors, and (2) the potential mediating roles of maternal depressive symptoms and parenting competence in linking stress and child internalizing and externalizing behaviors among rural Midwestern, low-income Latinx immigrant families, an understudied population.

Literature Review

The FSM model

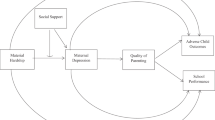

The family stress model (FSM) (Conger & Elder, 1994) provides a theoretical basis to help us understand the links between contextual stress and child internalizing and externalizing behaviors among rural Midwestern, low-income Latinx immigrant families. The model was originally developed to explain how economic hardship affected child adjustment among families who experienced the agricultural economic downtown in the 1980s in the rural Midwest (Conger & Conger, 2002). Although the FSM primarily focuses on economic stress, various environmental stressors are also applicable (Masarik & Conger, 2017). As the FSM posits, chronic or acute economic stress can disrupt parents’ emotional state and the quality of family interactions, which leads to difficulties in child adjustment (e.g., internalizing and externalizing behavior problems). More specifically, economic stress elevates parents’ risk for emotional distress (e.g., depression, anxiety). Parents’ emotional distress can then spill over to parenting behaviors, which in turn place children at risk for negative outcomes.

Economic pressure, parent acculturative stress and Latinx child behaviors

Economic pressure is “the day-to-day strains and hassles that unstable economic conditions create for families” (Masarik & Conger, 2017), which has been argued to play a central and critical role in influencing child outcomes (Conger et al., 1993). Studies using rural and national samples have demonstrated negative impacts of economic pressure on both internalizing behaviors (Conger et al., 1993, 2002; Robila & Krishnakumar, 2006) and externalizing behaviors (Conger et al., 1993, 2002; Neppl et al., 2016; Robila & Krishnakumar, 2006) of children at different developmental stages and from diverse ethnic backgrounds. Among Latinx children, the findings are similar (Dennis et al., 2003; White et al., 2015). For example, after controlling for family and social support, Santiago and Wadsworth (2011) found that more economic pressure was significantly associated with more internalizing and externalizing behaviors among low-income Latinx children.

Acculturative stress often stems from the process of adapting to a new culture while continuing to affiliate with one’s culture of origin (Concha et al., 2016). For Latinx immigrants, it can include the pressures of learning a new language and keeping the language of the family of origin, balancing conflicting cultural values and ways of behaving, parent-child acculturation conflicts etc. (Torres et al., 2012). In contrast to many studies focused on Latinx child-reported acculturative stress and their own outcomes (Cervantes et al., 2013; Schwartz et al., 2015), the relations between Latinx parent acculturative stress and their children’s outcomes are understudied (Leon, 2014). Among the few studies on parent acculturative stress and child outcomes, Leidy and colleagues (2009) found that parent acculturative stress was significantly associated with Mexican American children’s internalizing behaviors after controlling for the number of years parents resided in the US. Lorenzo-Blanco et al. (2016) investigated the longitudinal impacts of Latinx parent acculturative stress on child outcomes. Findings suggested that Latinx parent acculturative stress was indirectly linked to their children’s self-esteem, aggression, tobacco and alcohol use. Despite economic pressure and Latinx parent acculturative stress having shown positive links to child internalizing and/or externalizing behaviors, little research has considered Latinx child behavior outcomes in light of their parents’ experiences of both economic pressure and acculturative stress, or included multiple factors that may mediate or moderate the stress process (Nguyen, 2006).

The family stress process

Individual reactions to stress could serve as mediators between stressors and child outcomes (Greder et al., 2017). Maternal depression and parenting competence are two within-family processes that have often been linked to child behaviors. Mothers have reported symptoms of distress (e.g., depressive symptoms) when exposed to stressors such as economic pressure (Masarik & Conger, 2017) and acculturative stress (Zeiders et al., 2015). Distressed mothers have been shown to have reduced empathy and emotional responsiveness towards their children (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999), lower confidence and ability to care for and raise their children (Kiernan & Huerta, 2008), and to exhibit negative and hostile parenting behaviors when interacting with their children (Lovejoy et al., 2000). As a result, children, including Latinx children, who are parented by distressed mothers may be more likely to experience negative behaviors (Dennis et al., 2003; Goodman et al., 2011).

Parenting competence is related to parents’ confidence regarding their ability to raise their children successfully (Jones & Prinz, 2005). Exposure to stress lowers parenting competence (Jackson & Scheines, 2005). Migration to another country where cultural values and norms may differ can create additional challenges in parenting. For example, Martinez (2006) suggested that Latinx immigrant parents may experience increased frustration in unsuccessful establishment of authority and difficulties with communication and monitoring their children due to parent-child acculturation conflict. Research has also found that parents with low parenting competence were less likely to demonstrate parental involvement, monitoring and responsiveness, and more likely to use negative parenting practice (Shumow & Lomax, 2002), which in turn placed children at high risk for poor outcomes.

Current study

In the current study, we examined the relationships among economic pressure, parent acculturative stress, maternal depressive symptoms, parenting competence, and child internalizing and externalizing behaviors among rural Midwestern, low-income, Latinx immigrant families using data from the Iowa Rural Latino Family Project (Greder & Russell, 2017). Guided by the family stress model and prior literature, we predicted that higher levels of economic pressure and parent acculturative stress would be associated with higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms, which would link to lower parenting competence. Lower levels of parenting competence, in turn, would contribute to more child internalizing and/or externalizing behavior problems (see Fig. 1).

Methodology

Sample

Participants for this study were from a larger project that was focused on examining the health and well-being of rural low-income Latinx families in a Midwestern state (Greder & Russell, 2017). To participate in the larger study, participants had to meet the following criteria: (1) be mothers who were 18 years of age or older; (2) be first or second generation Latinx ; (3) have annual household income at or below 185% of the U.S. federal poverty level; (4) have at least one child 12 years of age or younger who lived with them at least 50% of the time; and (5) reside in one of the rural study communities. The sample for this study (N = 148) included only first generation Latinx mothers who responded to questions pertaining to parent acculturative stress and parenting competence, measures that were first introduced in Panel 1 Time 2 during 2013–2015 (P1T2; n = 49), and included in Panel 2 Time 1 during 2014–2017 (P2T1; n = 99). The demographic characteristics of the sample for this study are included in Table 1.

Sampling Procedure

Respondent driven sampling (RDS; Heckathorn, 2002), a nonprobability sampling method for recruiting populations who may be difficult to reach, and for whom sampling frames are not available, was used to recruit mothers from a friendship network of existing members into the study. Bi-lingual Latinx mothers were trained to recruit and interview participants. First, the interviewer in each study community identified three mothers who potentially met the study criteria and invited them to participate in the study. Mothers then completed an initial screening interview to ensure they met eligibility criteria for the study. If eligibility criteria were met, mothers were invited to participate in a two-hour in-person interview. Upon completion of the interviews, mothers were offered a $50 gift card for their participation. Then, mothers were provided three fliers that contained information about the study to distribute to other mothers who they believed met the study criteria. Mothers who received the fliers contacted the interviewer in their community if they were interested in participating in the study, and then a screening interview was scheduled and conducted in-person or via phone. If mothers were deemed eligible to participate in the study, a two-hour interview was scheduled and conducted in the language preferred by each mother (e.g., Spanish, English) in a location that was convenient, comfortable, safe, and ensured privacy (e.g., mothers’ homes, private conference room at the local extension office or library, family resource center). Most of the participants in this study chose to be interviewed in Spanish (90.2%; 9.8% in English). The interview protocol included demographic questions and questions from standardized instruments to assess stress and physical and mental health and well-being of the mothers and their children. Specific questions regarding behaviors of a randomly selected focal child in each family were also included. The University Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the associated institution approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from mothers before each interview.

Measures

Economic pressure. A modified version of the Personal Financial Wellness Scale (Prawitz et al., 2006) (8 items) was used to assess economic pressure. The first two items assessed the level of financial stress “today” and financial stressful feelings “in general.” Response options ranged from 1 (very low) to 5 (very high). The next two items asked about satisfaction and feelings about one’s financial situation. Likert-scale responses ranged from 1 (completely dissatisfied) to 5 (completely satisfied) and reverse coded into 1 (completely satisfied) to 5 (completely dissatisfied). These were followed by three items about difficulty in making ends meet. Response options were from 1 (never) to 5 (very frequently). The last item was about confidence in finding money to pay for a financial emergency that costs about $100. Likert-scale responses ranged from 1 (highly doubtful) to 5 (highly confident) and were reverse coded into 1 (highly confident) to 5 (highly doubtful). To create a latent economic pressure variable, three parcel measures were formed from the 8-item measure. A mean score was calculated for each parcel, with a higher mean score indicating a higher level of perceived economic pressure (Cronbach’s α = 0.83).

Parent acculturative stress. The abbreviated (17 item) Hispanic Stress Inventory - Immigrant Form (HSI-I; Cavazos-Rehg et al., 2006) was used to assess parent perceived acculturative stress. Statements were related to hassles that arise within the family context associated with conflicts regarding parental, familial and marital responsibilities (e.g., “My children have not respected my authority the way they should”) and outside the family context associated with occupational/economical and immigration challenges (e.g., “Because of my poor English people have treated me badly”). Mothers were asked to indicate whether or not they had experienced the stressful situation during the past three months (Yes or No). If her response was “Yes”, then she rated how worried or tense she was for each stressful situation on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all worried/tense) to 5 (extremely worried/tense). If her response was “No”, then the follow-up question was coded as 0. To create a latent parent acculturative stress variable, three parcel measures were formed from this 17-item measure. A mean score was calculated for each parcel, with a higher mean score indicating a higher level of mother perceived acculturative stress (Cronbach’s α = 0.84).

Maternal depressive symptoms. A shortened form of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Andersen et al., 1994) was used to assess mothers’ depression-related symptoms. Mothers were asked to give responses to 10 statements based on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Rarely or none of the time) to 3 (all the time). Example statements included “I was bothered by things that usually don’t bother me,” and “I was lonely.” Responses of the two positive statements, “I felt hopeful about the future” and “I was happy” were reverse coded as 0 (all the time) to 3 (rarely or none of the time). Because the item “I felt hopeful about the future” had negative corrected item-total correlation value after the reverse coding, thus indicating this item did not work well for our sample, it was omitted. To create a latent maternal depressive symptoms variable, three parcel measures were formed from this 9-item measure. A mean score was calculated for each parcel, with a higher mean score indicating more maternal depressive symptoms (Cronbach’s α = 0.83).

Parenting competence. A modified version of the Parenting Sense of Competency Scale (Gibaud-Wallston & Wandersman, 1978) was used to assess mothers’ perceptions of their competence in parenting. Mothers were asked to respond to sixteen statements based on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 6 (strongly disagree). Example statements included “Sometimes I feel like I’m not getting anything done” and “I meet my own personal expectations for expertise in caring for my child.” Responses for five positive statements (e.g., “If anyone can find the answer to what is troubling my child, I’m the one”) were reverse coded as 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Because the item “I meet my own personal expectations for expertise in caring for my child” had negative corrected item-total correlation value after the reverse coding, it was omitted. To create a latent parenting competence variable, three parcel measures were formed from this 15-item measure. A mean score was calculated for each parcel, with a higher score indicating a higher level of competence in parenting (Cronbach’s α = 0.70).

Child internalizing and externalizing behaviors. The Child Behavior Checklist 18 months − 5 years (Parent’s Report Form; CBCL 1½ − 5) (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) and the Child Behavior Checklist 6–18 years (CBCL 6–18) (Parent’s Report Form; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) were used to assess symptoms of internalizing and externalizing behaviors of the focal children. Internalizing behaviors include processes within oneself (e.g., anxiety, somatization, depression), and externalizing behaviors include actions in the external world (e.g., acting out, antisocial behavior, hostility, aggression) (American Psychological Association, n.d.). Example items of internalizing behaviors were “Feelings are easily hurt,” and “Too shy or timid.” Example items of externalizing behaviors were “Gets in many fights,” and “Drinks alcohol without parents’ approval.” Mothers provided their responses using a 3-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not true) to 2 (very true or often true). Raw scores of child internalizing and externalizing behaviors were computed first, and were then converted into gender and age normed T scores based on the Achenbach scoring protocol. Higher T scores reflected more symptoms of internalizing and externalizing behaviors. T scores that have values higher than 64 are in the clinical range of problem behaviors and referrals may be made for professional mental health evaluation (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000).

Control variables. Data collection panel and child age group were significantly correlated to the proposed mediating variables (e.g., depressive symptoms) and/or outcome variables (e.g., child internalizing behaviors). Therefore, data collection panel (1 = Panel 1, 0 = Panel 2) and child age group (1 = older child age group, 0 = younger child age group) were included as control variables when testing the conceptual model.

Data Analysis Plan

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations were computed using the SPSS 27.0 software package. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was estimated using the Mplus 7.0 software package. Latent variables with multiple indicators were employed as they tend to be more reliable than a single indicator (Kline, 1998). Considering the small study sample (N = 148) and no established subscales within the scales (e.g., economic pressure, depressive symptoms), we created “item parcels” containing three indicators per latent variable. Model goodness of fit was evaluated by Root Mean Square Error Approximation (RMSEA; good fit if value is below 0.05 and moderate fit if value is below 0.08) and Comparative Fit Index (CFI; good fit if value is above 0.95 and moderate fit if value is above 0.90). Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) procedure was used to handle missing data because it more accurately represents relationships among variables than does the list-wise deletion procedure for missing data (Conger et al., 2002).

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations among constructs

The means and standard deviations for all observed variables, and correlations among the variables are provided in Table 2. The three indicators of each latent variable were correlated significantly with one another. Indicators of economic pressure were positively associated with indicators of parent acculturative stress, maternal depressive symptoms, child internalizing behaviors, and negatively associated with the indicator of parenting competence. In other words, when Latinx immigrant mothers perceived more economic pressure, they experienced more stress from acculturation, more depressive symptoms, less competence in parenting, and reported more internalizing behaviors among their children. Indicators of parent acculturative stress were positively correlated with indicators of maternal depressive symptoms, child internalizing and externalizing behaviors, and negatively correlated with parenting competence. Specifically, when Latinx immigrant mothers experienced more acculturative stress, they were more likely to have more depressive symptoms, lower parenting competence and report more internalizing and externalizing behavior problems among their children. Indicators of maternal depressive symptoms were negatively associated with indicators of parenting competence, and positively associated with child internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Thus, Latinx immigrant mothers felt less competent as parents and reported more internalizing and externalizing behaviors among their children when they experienced more depressive symptoms. Parenting competence was negatively associated with child internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Thus, lower parenting competence among mothers was associated with more internalizing and externalizing behavior problems among their children.

Structural Equation analyses

The measurement model in this study provided an adequate fit to the data, χ2(48, N = 148) = 74.390, p < .05, CFI = 0.963, RMSEA = 0.061. Standardized loadings of the observed variables on the latent variables are shown in Table 3. All the loadings were highly significant.

Figure 2 shows the findings of our final model (after adding some additional paths suggested by the modification indices) and the standardized path coefficients. This model provided an adequate fit to the data, 𝜒2(83, N = 148) = 126.171, p < .05, CFI = 0.950, RMSEA = 0.059. As expected, higher levels of economic pressure and parent acculturative stress were significantly associated with higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms. Higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms were significantly associated with lower levels of parenting competence. Parenting competence was a significant predictor of child externalizing behaviors, but not child internalizing behaviors. Additionally, parent acculturative stress was directly linked to child internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Specifically, when Latinx immigrant mothers perceived higher levels of acculturative stress, they reported more internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors among their children. Parent acculturative stress also had a significantly negative association with parenting competence. Additionally, there was a significantly positive direct link between maternal depressive symptoms and child internalizing behaviors. The model accounted for 23.4% of the variance in maternal depressive symptoms, 16.2% of the variance in parenting competence, 35.7% of the variance in child internalizing behaviors, and 19.2% of the variance in child externalizing behaviors.

The indirect effects of contextual stress on child behaviors were tested with the 1000 bias corrected bootstrap sampling procedure in Mplus and 95% confidence intervals were used to determine the specific indirect effects. Table 4 presents the four significant indirect effects of stress on child behaviors: (1) economic pressure on child externalizing behaviors through maternal depressive symptoms and parenting competence, (2) economic pressure on child internalizing behaviors through maternal depressive symptoms, (3) parent acculturative stress on child externalizing behaviors through parenting competence, and (4) parent acculturative stress on child internalizing behaviors through maternal depressive symptoms.

Discussion

Guided by the FSM, we investigated the potential mediating roles that maternal depressive symptoms and parenting competence played in the relationship between specific stressors (i.e., economic pressure, parent acculturative stress) and the behaviors of Latinx immigrant children who lived in rural communities in a Midwestern state. Results confirmed the significant roles that maternal depressive symptoms and parenting competence play in relationships among economic pressure, parent acculturative stress, and child behaviors among this understudied population.

First, consistent with previous studies (Dennis et al., 2003; Zeiders et al., 2015), both economic pressure and parent acculturative stress were significantly related to maternal depressive symptoms. More specifically, higher levels of economic pressure and parent acculturative stress were associated with higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms. Second, while parent acculturative stress was both directly and indirectly related to parenting competence, economic pressure was only indirectly related to parenting competence through maternal depressive symptoms. Thus, economic pressure may not be associated with mothers’ parenting confidence in raising their children unless mothers experienced depressive symptoms due to the economic stress. In contrast, acculturative stress was associated with mothers’ parenting competence regardless of the presence of depressive symptoms. One possible explanation for this finding may be that the stresses manifested by economic pressure and acculturative stress may be different even though these two stressors were significantly correlated. For example, stress manifested from acculturation may be more complex and have multiple dimensions compared to stress manifested by economic pressure. Research has showed that Latinx mothers who experienced stress due to differences in acculturation among family members were more likely to report frustration and reduced confidence in parenting (Martinez, 2006). Third, consistent with prior findings (Goodman et al., 2011), maternal depressive symptoms were related to both child internalizing and externalizing behaviors. However, there was a difference in how maternal depressive symptoms were related to child internalizing and externalizing behaviors. While there was a direct association between maternal depressive symptoms and child internalizing behaviors, parenting competence fully mediated the relationship between maternal depressive symptoms and child externalizing behaviors. In a meta-analytic review of maternal depression and child psychopathology (Goodman et al., 2011), the authors suggest that different patterns of parenting help to explain how maternal depression relates differently to child internalizing behaviors versus externalizing behaviors. Maternal depressive symptoms undermine parenting (Dix & Meunier, 2009). Ineffective parenting (e.g., harsh, inconsistent parenting, inadequate supervision) has been particularly linked with child externalizing behaviors (Patterson et al., 1992). In contrast, children may be directly affected by their mothers’ symptoms of depression (e.g., sadness, angry outbursts, anxiety) during their interactions with their mothers, and in turn internalize problems. Lastly, consistent with prior research findings (Zeiders et al., 2016), we found direct links between parent acculturative stress and child internalizing and externalizing behaviors. This finding re-emphasizes the broad impacts of parent acculturative stress on Latinx parents themselves, their children, and the functioning of their families. These findings are particularly timely given the increases in economic and emotional stress and associated increases in child behavior problems experienced by numerous parents and their children across the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic (Barnett & Jung, 2021). Additionally, in a study of 135 Latinx immigrant parents conducted in 2020 in rural communities in a Midwestern state (Greder et al., 2020), over one-third (39.3%) of the Latinx immigrant households experienced food insecurity and one-fourth (25.2%) of the Latinx immigrant parents in the study experienced high depressive symptomology compared to 20.0% and 11.8% respectively in 2019, the year before the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Latinx immigrant parents in that study reported multiple worries about their families and children including worries related to family members becoming ill, reduced income, difficultes paying bills, isolation from family and friends, all of which made parenting more stressful and put children at high risk for behavior problems.

Strengths and Limitations

A major strength of this study is the inclusion of an understudied but fast-growing minority population residing in the rural Midwest. Additionally, the use of structural equation modeling (SEM) allows a simultaneous analysis of the relationships among economic and parent acculturative stressors, the family stress process, and child behaviors among rural low-income Latinx immigrant families. Findings affirmed the significant mediating roles that maternal depressive symptoms and parenting competence played between contextual stress (e.g., economic pressure, acculturative stress) and rural low-income Midwestern Latinx children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors.

Despite the strengths of this study, some limitations are important to acknowledge. First, data for this study were collected from a relatively small sample (N = 148) of Latinx immigrant mothers in one Midwestern state. Thus, generalizability of the findings is limited. Second, only self-report measures were used which could lead to shared method variance and enter bias into the study (Cutrona et al., 2011). Third, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits causal and directional inferences. This study was theoretically proposed. However, the findings lend further empirical support and are subject to reverse causality such that mothers having child(ren) with behavior problems may have lower parenting competence resulting from decreased effectiveness of parental communication and teaching, may report more maternal depressive symptoms (Gartstein & Sheeber, 2004), and may experience more challenges and higher stress levels than do their counterparts who do not have children with behavior problems. Lastly, even though parenting competence was assessed in this study, parenting behaviors, a key mediator in the theoretical framework that guided this study, was not included (as data were not collected).

Conclusions and future directions

This study provides a first look at how economic pressure, coupled with parent acculturative stress, is linked to child internalizing and externalizing behaviors through maternal depressive symptoms and parenting competence among an understudied population - low-income, Latinx families residing in rural Midwestern communities. Although much remains to be investigated about these associations, this exploratory study provides several implications for research, practice, and policy.

Future research may consider including a larger sample of Latinx immigrant families residing in rural Midwestern communities across multiple states, as well as comparing and contrasting data from Latinx families whose members were born in the US or in Latin America. Future research may also incorporate data collected from additional family members (e.g., fathers) and use multiple data collection techniques (e.g., observation, in-depth interviews). It is important to note that while the final model in this study suggested processes associated with child behaviors, causation and the direction of associations cannot be determined due to the cross-sectional nature of the data. Thus, the study findings should be interpreted with caution. Future studies should be carefully designed to assess the causal relationships between contextual stress, maternal depressive symptoms, parenting competence and child behavior problems. For example, they should focus on exploring longitudinal associations that include three or more time points, and that apply a social-interactional perspective to establish the causation among the study variables, while simultaneously accounting for potential influences of child, mother, and family characteristics.

Despite challenges to alleviate economic pressure among rural Midwestern Latinx immigrants who have low incomes and low education levels, efforts towards improving their financial well-being are still warranted. Direct strategies such as advocating for equitable wages and benefits and providing access to work-based income supplementation or assistance programs could improve families’ economic situation (Yoshikawa et al., 2012). Indirect strategies include assisting Latinx immigrant families in broadening their social networks, building human capital (e.g., English proficiency, literacy, vocational training), and increasing access to basic resources (e.g., public assistance e.g., SNAP, WIC to meet basic food needs; mental health services) (Greder et al., 2020; Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2016). Additionally, in light of findings related to increased economic and emotional stress among Latinx immigrant parents and their families during the COVID-19 pandemic, community-based parenting and family education programs, as well as social marketing messages, that help parents perceive increased control and social support may lead to reduced perceived stress.

Intervention and prevention programs intended to promote positive family functioning and children’s emotional and behavioral well-being among rural Midwestern Latinx communities may consider utilizing findings from this study. For example, family serving programs or services in rural Midwestern communities can develop and help Latinx immigrant families identify and access affordable, culturally responsive mental health resources and services (Greder et al., 2017), as well as develop and provide culturally tailored information and educational programs that promote parenting knowledge and skills that strengthen parenting competence.

Given the direct association between maternal acculturative stress and child internalizing and externalizing behaviors, practices and policies that aim to reduce Latinx immigrant mothers’ acculturative stress may be particularly useful. Administrators of rural programs and services may want to identify tools to briefly and effectively assess parent acculturative stress among rural Latinx immigrant families, and help them identify strategies to cope with acculturative stress. Practitioners could also assist families in increasing their knowledge of U.S. norms and policies, and learn how to navigate various systems (e.g., education, health care, social support). Structural level changes such as discrimination may also lead to acculturative stress. Media outlets (e.g., radio PSAs, bulletin boards) and organizations (e.g., United Way, schools, health care and faith organizations) can advocate for diversity and inclusion via messages they communicate within their organizations and in their communities. Government and non-government agencies can provide more culturally responsive resources and services to help rural Midwestern Latinx immigrant parents and their children build trust with others in their communities and to identify coping strategies to manage acculturative stress.

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. (2001). ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. Aseba Burlington, VT

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2000). Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms and profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research center for children, youth, & families

American Psychological Association (n.d.). APA Dictionary of Psychology – externalizing-internalizing. Retrieved from https://dictionary.apa.org/externalizing-internalizing

Andersen, E. M., Malmgren, J. A., Carter, W. B., & Patrick, D. L. (1994). Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 10(2), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(18)30622-6

Barnett, W. S., & Jung, K. (2021). Seven Impacts of the Pandemic on Young Children and their Parents: Initial Findings from NIEER’s December 2020 Preschool Learning Activities Survey. New Brunswick, NJ: National Institute for Early Education Research

Berry, J. W. (1980). Acculturation as varieties of adaptation. In A. M. Padilla (Ed.), Acculturation: Theory, models, and some new findings (pp. 9–25). Boulder, CO: Westview Press

Caetano, R., Ramisetty-Mikler, S., Caetano Vaeth, P. A., & Harris, T. R. (2007). Acculturation stress, drinking, and intimate partner violence among Hispanic couples in the US. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22(11), 1431–1447. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260507305568

Cavazos-Rehg, P. A., Zayas, L. H., Walker, M. S., & Fisher, E. B. (2006). Evaluating an abbreviated version of the Hispanic stress inventory for immigrants. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 28(4), 498–515. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986306291740

Cervantes, R. C., Padilla, A. M., Napper, L. E., & Goldbach, J. T. (2013). Acculturation-related stress and mental health outcomes among three generations of Hispanic adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 35(4), 451–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986313500924

Concha, M., Sanchez, M., Rojas, P., Villar, M. E., & De La Rosa, M. (2016). Differences in acculturation and trajectories of anxiety and alcohol consumption among Latino mothers and daughters in South Florida. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 18(4), 886–895. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-015-0277-y

Conger, R. D., Conger, K. J., Elder, G. H., Lorenz, F. O., Simons, R. L., & Whitbeck, L. B. (1993). Family economic stress and adjustment of early adolescent girls. Developmental Psychology, 29(2), 206–219. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.29.2.206

Conger, R. D., & Elder, G. H. Jr. (1994). Families in troubled times: Adapting to change in rural America. Social Institutions and Social Change (p. ED391634). ERIC

Conger, R. D., & Conger, K. J. (2002). Resilience in Midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective, longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 361–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00361.x

Conger, R. D., Wallace, L. E., Sun, Y., Simons, R. L., McLoyd, V. C., & Brody, G. H. (2002). Economic pressure in African American families: a replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental psychology, 38(2), 179

Cutrona, C. E., Russell, D. W., Burzette, R. G., Wesner, K. A., & Bryant, C. M. (2011). Predicting relationship stability among midlife African American couples. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 79(6), 814

D’Anna-Hernandez, K. L., Aleman, B., & Flores, A. M. (2015). Acculturative stress negatively impacts maternal depressive symptoms in Mexican-American women during pregnancy. Journal of Affective Disorders, 176, 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.036

Dennis, J. M., Parke, R. D., Coltrane, S., Blacher, J., & Borthwick-Duffy, S. A. (2003). Economic pressure, maternal depression, and child adjustment in Latino families: An exploratory study. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 24(2), 183–202. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023706424725

Dix, T., & Meunier, L. N. (2009). Depressive symptoms and parenting competence: An analysis of 13 regulatory processes. Developmental Review, 29(1), 45–68

Economic Research Service (2018, November). Rural America at a glance. United States Department of Agriculture. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/90556/eib-200.pdf?v=7377.7

Gartstein, M. A., & Sheeber, L. (2004). Child behavior problems and maternal symptoms of depression: A mediational model. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 17(4), 141–150

Gibaud-Wallston, J., & Wandersman, L. P. (1978). Parenting sense of competence scale. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Goodman, S. H., Rouse, M. H., Connell, A. M., Broth, M. R., Hall, C. M., & Heyward, D. (2011). Maternal depression and child psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14(1), 1–27. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1

Goodman, S. H., & Gotlib, I. H. (1999). Children of depressed parents: Mechanisms of risk and implications for treatment. Psychological Review, 106(3), 458–490

Greder, K. and Russell, D. (2017). Iowa Rural Latino Family Project: Exploration of Individual and Family Influences on Health and Well-being. Iowa Agriculture and Home Economics Experiment Station [Project No. IOW04016, Kimberly Greder, PI]. Ames, Iowa.

Greder, Peng, C., Doudna, K. D., & Sarver, S. L. (2017). Role of fam?ily stressors on rural low-income children’s behaviors. Child & Youth Care Forum, 46(5), 703–720. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-017-9401-6

Greder, K., Kim, D., Williams, E., and Bao, J. (2020). COVID-19 and Rural Iowa Latinx Immigrant Families. Presentation at the Human Sciences Extension and Outreach Monthly Professional Development Meeting. Webinar. Iowa State University, Ames, IA.

Heckathorn, D. D. (2002). Respondent-driven sampling II: deriving valid population estimates from chain-referral samples of hidden populations. Social Problems, 49(1), 11–34. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2002.49.1.11

Jackson, A. P., & Scheines, R. (2005). Single mothers’ self-efficacy, parenting in the home environment, and children’s development in a two-wave study. Social Work Research, 29(1), 7–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/29.1.7

Jones, T. L., & Prinz, R. J. (2005). Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and child adjustment: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(3), 341–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2004.12.004

Kandel, W., & Cromartie, J. (2004, May). New patterns of Hispanic settlement in rural America. United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Services. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/47077/rdrr-99.pdf?v=0

Kiernan, K. E., & Huerta, M. C. (2008). Economic deprivation, maternal depression, parenting and children’s cognitive and emotional development in early childhood. The British Journal of Sociology, 59(4), 783–806. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2008.00219.x

Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: The Guilford Press

Leidy, M. S., Parke, R. D., Cladis, M., Coltrane, S., Duffy, S., & Murry, V. M. (2009). Positive marital quality, acculturative stress, and child outcomes among Mexican Americans. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71(4), 833–847. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00638.x

Leon, A. L. (2014). Immigration and stress: The relationship between parents’ acculturative stress and young children’s anxiety symptoms. Inquiries Journal, 6(3)

Lorenzo-Blanco, E. I., Meca, A., Unger, J. B., Romero, A., Gonzales-Backen, M., Piña-Watson, B. … Schwartz, S. J. (2016). Latino parent acculturation stress: Longitudinal effects on family functioning and youth emotional and behavioral health. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(8), 966–976. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000223

Lovejoy, M. C., Graczyk, P. A., O’Hare, E., & Neuman, G. (2000). Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(5), 561–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00100-7

Martinez, C. R. Jr. (2006). Effects of differential family acculturation on Latino adolescent substance use. Family Relations, 55(3), 306–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2006.00404.x

Masarik, A. S., & Conger, R. D. (2017). Stress and child development: A review of the Family Stress Model. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.008

May, S. F., Flores, L. Y., Jeanetta, S., Saunders, L., Valdivia, C., Arévalo Avalos, M. R., & Martínez, D. (2015). Latina/o immigrant integration in the rural Midwest: Host community resident and immigrant perspectives. Journal of Latinx Psychology, 3(1), 23–39

Neppl, T. K., Senia, J. M., & Donnellan, M. B. (2016). Effects of economic hardship: Testing the family stress model over time. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(1), 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000168

Nguyen, H. H. (2006). Acculturation in the United States. In D. L. Sam, & J. W. Berry (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology (pp. 311–330). New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511489891.024

Patterson, G. R., Reid, J. B., & Dishion, T. J. (1992). A social learning approach, vol. 4: Antisocial boys. Eugene, OR: Castalia

Prawitz, A. D., Garman, E. T., Sorhaindo, B., O’Neill, B., Kim, J., & Drentea, P. (2006). Incharge financial distress/financial well-being scale: Development, administration, and score interpretation.Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 17(1)

Raffaelli, M., & Wiley, A. R. (2012). Challenges and strengths of immigrant Latino families in the rural Midwest. Journal of Family Issues, 34(3), 347–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X11432422

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (2020). September-October). The Impact of Coronavirus on Households Across America. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2020/09/the-impact-of-coronavirus-on-households-across-america.html

Robila, M., & Krishnakumar, A. (2006). Economic pressure and children’s psychological functioning. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 15(4), 433–441

Santiago, C. D., & Wadsworth, M. E. (2011). Family and cultural influences on low-income Latino children’s adjustment. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40(2), 332–337

Schwartz, S. J., Unger, J. B., Baezconde-Garbanati, L., Zamboanga, B. L., Lorenzo-Blanco, E. I., Rosiers, D. … Piña-Watson, S. E., B. M (2015). Trajectories of cultural stressors and effects on mental health and substance use among Hispanic immigrant adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(4), 433–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.12.011

Shumow, L., & Lomax, R. (2002). Parental efficacy: Predictor of parenting behavior and adolescent outcomes. Parenting: Science and Practice, 2(2), 127–150

Smokowski, P. R., & Bacallao, M. L. (2006). Acculturation and aggression in Latino adolescents: A structural model focusing on cultural risk factors and assets. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34, 657–671

Torres, L., Driscoll, M. W., & Voell, M. (2012). Discrimination, acculturation, acculturative stress, and Latino psychological distress: A moderated mediational model. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18(1), 17

U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service (2021, June 17). Rural poverty & well-being. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-poverty-well-being/#demographics

White, R. M. B., Liu, Y., Nair, R. L., & Tein, J. Y. (2015). Longitudinal and integrative tests of family stress model effects on Mexican origin adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 51(5), 649–662. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038993

Yoshikawa, H., Aber, J. L., & Beardslee, W. R. (2012). The effects of poverty on the mental, emotional, and behavioral health of children and youth: Implications for prevention. American Psychologist, 67(4), 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028015

Zeiders, K. H., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Jahromi, L. B., Updegraff, K. A., & White, R. M. (2016). Discrimination and acculturation stress: A longitudinal study of children’s well-being from prenatal development to 5 years of age. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 37(7), 557–564. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000321

Zeiders, K. H., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Updegraff, K. A., & Jahromi, L. B. (2015). Acculturative and enculturative stress, depressive symptoms, and maternal warmth: Examining within-person relations among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers. Development and Psychopathology, 27(1), 293–308. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579414000637

Funding

This work is funded by Iowa Agriculture and Home Economics Experiment Station, Ames, Iowa and Iowa State University Extension and Outreach Strategic Initiative. Informed consent was obtained from each partipant prior to their participation in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests:

The authors declare that they have no known conflicts of interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bao, J., Greder, K. Economic Pressure and Parent Acculturative Stress: Effects on Rural Midwestern Low-Income Latinx Child Behaviors. J Fam Econ Iss 44, 490–501 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-022-09841-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-022-09841-4