Monday, June 1, 2020, was perhaps not the worst day in American civil-military relations. The US Army didn’t kill, capture or torture citizens (see Lindsay Cohn’s article for some history and the legalities of all of this). But because the events of the day (see below), especially the use of force to create a photo op, broke so many norms of American civil-military relations, it was perhaps the worst day for the crucial relationship since veterans marched on Washington during the Great Depression.

Here’s where things have gone very wrong:

Secretary of Defense Mark Esper—the person with responsibility for managing the civil-military relationship, the most senior civilian focused on defense—referred to Minneapolis as a “battlespace.” That only makes sense if American citizens are the adversary. It was an awful, awful thing to say, because it means that the US military, regulars, or National Guard are at war with civilians. Esper has tried to walk back his statement, but the damage has been done.

Senators and Representatives on the respective Armed Services committees play a key role in overseeing the armed forces. One of the key players on the Senate Armed Services Committee, Tom Cotton, called on the US regular troops to enter the fray, holding back nothing, and giving no quarter—which means killing those who surrender. Everyone pointed out this would be a war crime. Given that the GOP has a majority in the Senate, don’t expect much serious oversight coming from there, as Cotton and his peers are unlikely to let the agenda of that committee drift towards doing its responsibilities.

The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff is senior adviser to the President and the Secretary Defense but has no command authority except over the Joint Staff—a group of unarmed staffers (I didn’t see a weapon in my year in the Pentagon on the Joint Staff except by troops from elsewhere guarding the building). Yet, Trump said that General Mark Milley was in command of the effort. Making it appear that way, Milley walked around the aftermath of the ejection of protestors near the White House, wearing his Army Combat Uniforms—the uniform officers wear when engaged in operations, not the usual spiffy uniform worn when advising the President. Even if Milley was not in command, he appeared to be so.

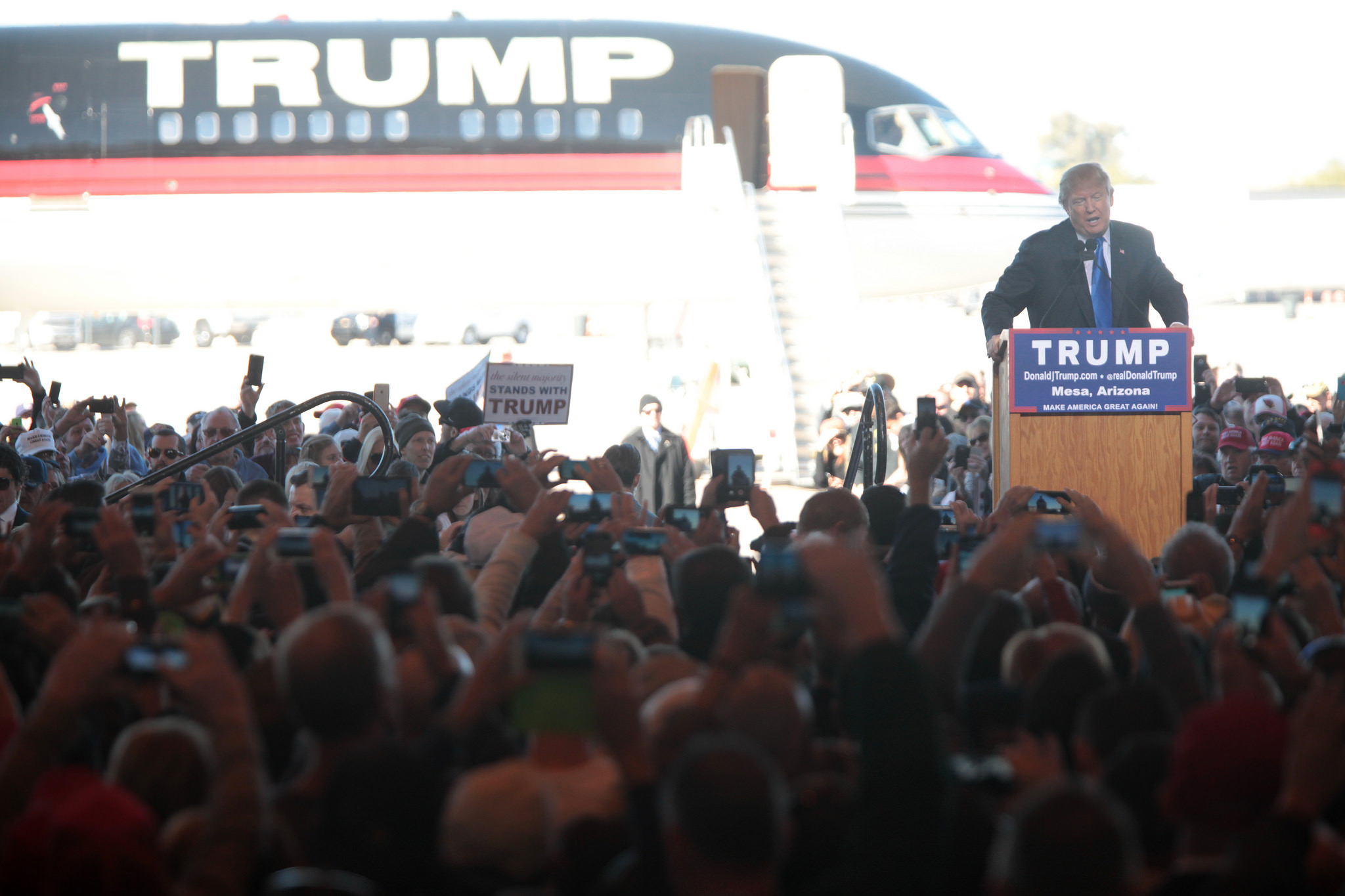

The President of the United States, the commander-in-chief, abused his authority to deploy US forces—National Guard and maybe Regular—for a photo op. At the time of writing, we still do not have clarification about who were flying Blackhawk helicopters to attempt to disperse—or intimidate—crowds, but it came clearly at the request of Trump so that he could hold a bible in front of the vandalized church—despite the preferences of those who run that church. Does the President have the authority to do this? According to Lindsay Cohn: mostly, yes. But abuse of power is when one uses their power in ways that are inappropriate—and using the military for a photo op while squelching the first amendment rights of peaceful protesters is clearly very wrong.

The media and the public are the last components of civilian control of the armed forces. No, they are not “in control” of the military, but they play a vital role in the civilian-military relationship. The media help to shine a spotlight when either the civilians, the military, or both engage in ways that harm civil-military relations. The media have been doing their job this weekend, despite being under attack by police forces across the country. Why attack the media? Because it is much harder to hold the police accountable if we cannot see and hear what they are doing. The public also plays a vital role—sending signals to their representatives about what is acceptable (or not), and engaging in protest if the politicians do not act. The vast majority of citizens involved have been engaged in protest, including civil disobedience. This weekend, there was a survey that showed the vast majority of Americans on the same side, horrified by the murder of George Floyd. Thus far, the photo op has not moved Americans towards supporting Trump’s calls for “domination” and the deployment of the US army on American streets.

Retired military officers are often louder than civil-military experts want them to be. Now? We see unprecedented criticism by recent Chairmen of the Joint Chiefs of Staff of the administration and of the military’s leadership, but this time, the experts on civil-military relations are not taking them to task.

Civil-military relations are broken. Not irreparably so, but that may still happen. The big questions ahead are:

- If Trump insists on sending troops to states where governors don’t want them, will they go? When leaders seek to use the military to repress, the military has a choice not to leave their bases. On Monday, elements left their bases for operations in DC, which has a special status, seen essentially as federal property. While many lines have been crossed, sending regular US forces into hostile states would be a big red line.

- What will Congress do? The Chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, Adam Smith, vowed to bring the Secretary of Defense and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to testify.

- How will the public react? The US military, like the armed forces of many democracies, is one of the most popular institutions. Why? In part, because it is seen as non-partisan, whereas most other institutions are seen as partisan, which, combined with polarization, leads to one part or another or both of America disliking it. If the US military jumps in, doing Trump’s bidding, public support of the armed forces will surely drop. It may already be happening thanks to this weekend’s events.

Monday was the worst day in American civil-military relations in recent memory. And it may get worse.