- Sea anemones were thought to be a rare fossil because of their softness, but paleontologists found countless fossils had been in plain sight.

- Fossils from a northern Illinois creek once thought to be jellyfish are anemones.

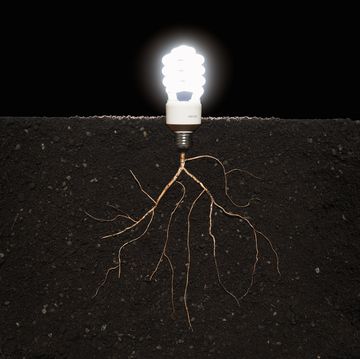

- By burying their bodies in mud, the anemones helped preserve themselves as fossils for later research.

Paleontologists flipped fossilized jellyfish over and realized something quite fascinating: The fossils weren’t of jellyfish at all, but were in fact a rarity in the underwater world—fossils of sea anemones.

While a sea anemone is nothing rare, fossil versions are highly uncommon. For a long time, we thought their squishy bodies couldn’t fossilize, but apparently, we’ve had sea anemone fossils hiding in plain sight for decades.

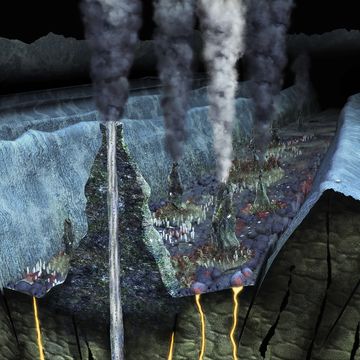

The specimens in question come from the Mazon Creek fossil deposits of Northern Illinois, an ancient delta that preserved millions of soft-bodied organisms when they were buried rapidly in muddy sediments. In a Papers in Paleontology study from the University of Illinois Chicago, paleontologist Roy Plotnick and colleagues show that what were previously tbelieved to be jellyfish fossils were really anemones.

All it took was flipping the jellyfish to make the discovery.

“Anemones are basically flipped jellyfish,” Plotnick says in a press release. “This study demonstrates how a simple shift of a mental image can lead to new ideas and interpretations.”

The Mazon Creek fossils were so common to local recreational fossil collectors that they were dubbed “the blob” and many were thrown out or sold at flea markets. In 1979, after a museum donation of a group of these fossils, a professor from Bradley University declared them jellyfish fossils. They were described as unlike any other living jellyfish, with a “curtain” that hung off the umbrella-like bell on the top of the organism. The new paper took a fresh look at this 1979 research.

“It quickly became obvious that not only it wasn’t a jellyfish [sic], but turned upside down it was clearly an anemone, probably one that burrowed into the seafloor,” Plotnick says. “The ‘bell’ was actually an expanded muscular foot used to wiggle the anemone into the seafloor.”

The researchers say that many of the fossils look like decomposing blobs, “like a piece of used gum on the sidewalk.” Some are so intricately preserved they can see the muscles that the anemones used to bend and contract their bodies.

“These fossils are better preserved than Twinkies after an apocalypse,” James Hagadorn, study co-author and Denver Museum of Nature and Science fossil preservation expert says in a news release. “In part that’s because many of them burrowed into the seafloor as they were being buried by a stormy avalanche of mud.”

Tim Newcomb is a journalist based in the Pacific Northwest. He covers stadiums, sneakers, gear, infrastructure, and more for a variety of publications, including Popular Mechanics. His favorite interviews have included sit-downs with Roger Federer in Switzerland, Kobe Bryant in Los Angeles, and Tinker Hatfield in Portland.