-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Quan D Mai, Unclear Signals, Uncertain Prospects: The Labor Market Consequences of Freelancing in the New Economy, Social Forces, Volume 99, Issue 3, March 2021, Pages 895–920, https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soaa043

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The advent of various types of contingent jobs complicates selection criteria for full-time employment. While previous studies analyzed the penalties associated with other forms of contingent work, the labor market consequences of freelancing have been overlooked. I argue that freelancing works have features of both “good” and “bad” jobs, transcend the demarcation between “primary” and “secondary” sectors implied by segmentation theorists, and thus embed uncertainty around their categorization and meaning. Drawing on the “signal clarity” concept from management scholarship, I extend existing sociological works on employer perceptions of candidates by proposing a model to theorize how a history of freelancing affects workers’ prospects at the hiring stage. I present results from two interrelated studies. First, I use a field experiment that involves submitting nearly 12,000 fictitious resumes to analyze the causal effect of a freelancing work history on the likelihood of getting callbacks. The experiment reveals that freelancing decreases workers’ odds of securing full-time employment by about 30 percent. Second, I use data from 42 in-depth interviews with hiring officers to illustrate two mechanisms that could account for that observed effect. Interview data demonstrate that freelancing sends decidedly unclear competence signals: employers are hesitant to hire freelancers not because these candidates lack skills but because verifying these skills is difficult. Freelancing also sends clearer and negative commitment signals. This study sheds new lights on labor market segmentation theory and deepens our understanding of how nonstandard work operates as a vehicle for inequality in the new economy.

Introduction

The US labor market has undergone fundamental transformations in recent decades, with important structural changes in the economy giving rise to the proliferation of precarious work (Kalleberg 2000, 2018). As the Karl Polanyian pendulum swings away from the period of relative security and toward the age of market-driven flexibility, a substantial number of part-time, temporary workers, and independent contractors, or freelancers,1 have arisen as important segments of the new precariat (Kalleberg 2009). The emergence of the nonstandard workforce and the characteristics of the work performed in this segment complicate employers’ selection criteria (Bills, DiStasio, and Gërxhani 2017) and raise theoretical questions about how these jobs affect subsequent employment prospects for workers.

Two competing theoretical perspectives offer insights into this question. The integrational labor market theory (Giesecke and Groß 2003; Schmid and Gazier 2002) predicts that nonstandard employment facilitates the transition to standard jobs because contingent workers benefit from an efficient market where employers flexibly test candidates’ skills on the job rather than relying on their productivity signals at hiring interface. Alternatively, having originated from the dual labor market theory (Doeringer and Piore 1985), the labor market segmentation perspective dichotomizes the economy into two separate segments―a primary and a secondary sector―with little mobility between the two. In the primary sector, jobs are stable, well-compensated, and relatively autonomous and provide good benefits. By contrast, workers in the secondary sector suffer from employment insecurity, poor wages, low autonomy, and lack of benefits and statutory protections. This perspective contends that nonstandard workers belong to the secondary segment, in which they have limited opportunities to transition to the primary sector (Gash 2008; Polavieja 2003). The two theories thus offer competing hypotheses about nonstandard workers’ prospects for transitioning to regular employment. Kalleberg (2000, 349) notes that the extent to which nonstandard workers can secure permanent jobs is an “unresolved issue.”

I argue that by focusing on part-time and temporary workers, scholarship in this debate undertheorizes heterogeneity in the nonstandard workforce and overlooks the increasing number of freelance workers. By freelancers, I mean self-employed workers who operate entirely on a project-to-project basis do not have a constant employer, do not have any employees, and are not primarily affiliated with staffing agencies. This definition excludes self-employed entrepreneurs who hire other workers, because their working entity is a small business that likely faces different experiences of precarity. Freelancers merit scholarly attention both for practical and theoretical reasons. Practically, freelancers play a large role in the nonstandard workforce. A recent survey found that out of 57 million Americans who engaged in some types of nonstandard employment, 28 percent considered themselves “full-time freelancers” (Ozimek 2019). Theoretically, freelancing is worth analyzing because this employment arrangement has characteristics that transcend the rigid classification that segmentation theory implies. Freelancers tend to include more high-skilled and in-demand workers than other nonstandard subgroups like temporary and on-call workers (Gleason 2006; Katz and Krueger 2019). Higher skills garner higher salaries: median weekly earnings for independent contractors are higher than for on-call and temporary agency workers and are similar to earnings for workers with traditional arrangements (BLS 2018). Katz and Krueger (2019, 402) report that independent contractors are paid more per hour than traditional employees. Compared to temporary workers, freelancers do not rely on employment intermediaries and have considerable autonomy over work schedules and processes (Felfe 2008; Osnowitz 2010). However, freelancing also has features of jobs typically seen in the peripheral sector. Uneven flows of revenue streams and new projects can subject freelancers to cycles of feast-or-famine, with stints of unemployment in-between. Moreover, freelancers are typically ineligible for employer-provided benefits. Freelancing is thus a hybrid employment arrangement, simultaneously exhibiting characteristics of jobs in the primary sector (high skill, pay, and autonomy) and secondary sector (low security, meager benefits). Freelancing consequently embeds high uncertainty around its meaning and grouping. Existing fieldwork demonstrates that the lack of a well-defined social categorization puts freelancers in social conditions “riddled with ambiguity” (Barley and Kunda 2006, 176; Osnowitz 2010). Analyzing opportunity structures that shape careers of workers in this relatively ambiguous group thus complicates segmentation theory and contributes to the debate about nonstandard worker mobility. In sum, given the sociological and practical significance of the issue, it is important to theorize freelancing and the labor market opportunity structures associated with this mode of employment.2

To theorize labor market opportunity structures associated with a history of freelancing, I rely on and contribute to sociological models of employer appraisal of applicants. Sociologists use different variations of signaling theories to show how gatekeepers evaluate applicants by activating widely held cultural beliefs associated with candidates’ attributes, and such beliefs can lead to direct and biased evaluation of candidates’ competence and commitment (Correll, Benard, and Paik 2007). A crucial assumption of existing models is that employers can appraise applicants’ attributes when these characteristics send clear signals, meaning that the attributes of interest have clear-cut sociocultural boundaries and relatively unambiguous cultural beliefs surrounding them. Labor market signals, however, vary along the clarity spectrum. Some signals are ambiguous and do not fit neatly into theoretically derived ideal types. The potential heterogeneity in the ways in which these signals can be interpreted constitutes a missing aspect of how labor market penalties, and discrimination more broadly, are theorized. How can extant models be extended to account for attributes that send unclear signals? To fill this theoretical gap, I draw on the concept of signal clarity from management scholars (Connelly et al. 2011; Sanders and Boivie 2004) to extend existing sociological models of employers’ applicant appraisals. I argue that the signal receptors’ ability to derive expectations about the signal senders’ capabilities depends on the clarity of the signal. Further, I incorporate insights from the emerging sociological literature that builds on cognitive science and decision theory (Bruch and Feinberg 2017; Bruch and Swait 2019) to illustrate the mechanisms through which an unclear signal can dampen the odds of a signal sender being selected at the hiring stage. I argue that by conveying ambiguous information that is challenging to interpret, and, thereby, increasing the cognitive efforts required by signal readers, candidates that send unclear signals about their capabilities run the risk of being eliminated at the screening stage. Using the case of freelancers, a group whose categorization is not well-classified and whose cultural meanings are relatively ambiguous, I illustrate how signal clarity, or a lack thereof, operates as a crucial factor shaping employers’ assessments of candidates, which subsequently impacts jobseekers’ mobility prospects in real-world settings.

My research asks two questions: “Is there a labor market penalty associated with a history of freelancing?” and “What are the mechanisms that could account for the effect of freelancing on workers’ subsequent labor market outcomes?” This paper is the first to analyze freelancers’ labor market prospects and explore the mechanisms that underlie such outcomes. I conducted two interrelated studies to understand how much of a disadvantage a history of freelancing carries when workers attempt to reintegrate into the full-time workforce and why such penalties exist. For the first study, I submitted nearly 12,000 fictitious resumes to real job openings in 50 urban labor markets. I randomly assigned applicants’ latest employment histories to full-time employment, freelancing, or unemployment. This experimental manipulation allowed for estimations of the causal effect of a freelancing history on workers’ career mobility. For the second study, I conducted semi-structured interviews with 42 hiring officers to gauge their perceptions of freelancing applicants. The evaluators’ perceptions illuminate how variation in signal clarity could shape mechanisms that likely account for the disadvantage observed in the field experiment.

This research makes several contributions. First, it assesses labor market opportunity structures associated with freelancers, an overlooked segment of the precarious workforce. This issue is significant because, on the demand side, employers are increasingly hiring from external labor markets and, on the supply side, many freelancers are pursuing organizational careers due to the inherently precarious nature of independent contracting. This contribution is critical considering the emerging discourses about the “1099s,” “gig,” or “on-demand” economy. Second, it extends sociological theories of employment discrimination by expanding models of employer perception and behavior to accommodate a wider range of applicants’ attributes, which can vary in terms of the clarity that their signals convey. Third, this research provides a methodological contribution. Extant scholarship in the debate between the integration and segmentation perspectives relies on survey data (see Gash 2008; Giesecke and Groß 2003). This reliance limits the ability to analyze employer perception of nonstandard workers, eliminate omitted variable bias, and make causal claims (see Pedulla 2016). The field experiment in this study permits estimates of the causal effect of freelancing on labor market outcomes. The in-depth follow-up interviews with employers then yield rich data to unpack the mechanisms that underlie such effect. This study’s mixed-methods approach—analyzing employers’ behavior with experimental data and their perception with interview data—provides a holistic view of how nonstandard work history operates at the hiring stage.

The paper proceeds as follows. The next section reviews the model that sociologists use to analyze how competence and commitment mediate the linkages between candidates’ signal-sending attributes and labor market outcomes and then shows how that model can be extended to account for unclear signals. I then outline reasons why freelancers would seek full-time employment and explore how signal clarity might shape employer perceptions of freelancers. Thereafter, I present the designs and results of the field experiment and in-depth interviews. The last section of the paper discusses the findings, explains their implications, and suggests directions for future research.

Signaling Theory, Competence, and Commitment

In the original formulation of signaling theory, employers are inundated with a large number of applications for any given vacancy and lack information about candidate quality. In order to reduce information asymmetry, employers rely on various candidate characteristics that could yield predictions about their productivity (Connelly et al. 2011). In that model, applicants send signals of their activities and attributes to employers. The signal recipients use those signals to generate predictions of signalers’ competence and values. This appraisal process shapes subsequent behaviors of employers, who can decide to approve or terminate candidacies (Spence 1973). Sociologists extend several variants of signaling theories to analyze how applicant activities, such as unemployment, underemployment, and labor market opt-out (Pedulla 2016; Weisshaar 2018), and attributes, such as gender, education, race, and parental status (Correll et al. 2007; Gaddis 2014; Quadlin 2018), might send signals about performance capacity and thus employability to employers.

Scholars theorize that performance capacity has at least two dimensions: competence and commitment (Correll et al. 2007; Pedulla 2016). Employers prefer candidates with a demonstrated record of competence, meaning ones who have attributes that might signal their ability to keep their skills updated. While the construct of competence stems from signaling theory, commitment emerges from the ideal worker norm (Turco 2010). This perspective maintains that organizational gatekeepers value workers who can signal their willingness to work longer hours, maintain full-time employment regardless of personal circumstances, and fully devote to the organization. The abilities of candidates to signal competence and commitment are seen as decisive factors shaping their employability. Correll et al. (2007) showed that evaluators consider mothers less competent and less committed than non-mothers. Pedulla (2016) demonstrated that employer perception of competence and commitment mediates the effect of mismatched employment histories on interview recommendations. These studies showed how competence and commitment are crucial mechanisms mediating the association between workers’ attributes or activities and their labor market outcomes.

Incorporating Signal Clarity

Existing sociological models suggest a direct linkage between applicant activities/attributes and employer evaluation, provided the signal-sending attributes are “believed to be directly relevant to the task at hand” (Correll et al. 2007, 1301). The core assumption of this model is that employers draw directly on candidates’ characteristics to make judgments about their capability to perform and to commit to the hiring firm. While previous studies generated important insights and advanced the field theoretically, they are not without limitations. The empirical attributes that existing models tested, such as gender, social class, educational credentials, unemployment, and parental status, are relatively well-understood constructs with generally clear surrounding sociocultural norms. A key feature of existing models is that employers can derive performance expectations when an attribute “has attached to it widely-held beliefs in the culture” (Correll et al. 2007, 1301). However, not all labor market signals are clear and have universally understood meanings. How generalizable are these models to attributes that embed a higher level of uncertainty, do not fit into theoretically predicted categories, and send noisier signals?

I argue that the existing model in the sociology of labor markets linking signalers’ attributes to signal receivers’ evaluation undertheorizes the signal itself, specifically the heterogeneity in signal clarity. To fill this gap, I bring in insights on signal clarity from the management and organizational behavior literature. Although originally theorized in the hiring context (Spence 1973), signaling theory has been imported and extended by management scholars to shed light on various processes, such as how organizations navigate uncertainty in the contexts of evaluating young firms (Sanders and Boivie 2004), timing acquisitions (Warner, Fairbank, and Steensma 2006), and changing dividend policies (Kao and Wu 1994). Building on Heil and Robertson (1991), I define “signal clarity” as the degree to which signals are unambiguous, have a known and verifiable origin, and can be evaluated quickly with minimum errors by signal recipients. Whereas existing works propose that competence and commitment mediate the association between attributes and outcomes, I propose an extended model where signal clarity influences the linkages between attributes and perceptions of competence and commitment, which then affect labor market outcomes. The evaluators’ ability to appraise signals that workers’ attributes send depends on how clear such signals are. A clear signal allows the recipient to make a more precise attribution of the sender’s underlying quality. By contrast, receivers need more effort to decipher and more time to evaluate an unclear signal, which can decrease the chance of a signal sender being chosen.

How exactly do the efforts and time needed for the evaluator to appraise an unclear signal reduce the odds of the signaler being selected? The emerging sociological literature on decision-making informs this process. Building on decision science, Bruch and colleagues advanced choice set formation model. This perspective maintains that when tasked with making decisions in various social arenas, individuals often have to face the cognitively taxing assignment of choosing between large numbers of alternatives (Bruch, Feinberg, and Lee 2016; Bruch and Feinberg 2017; Bruch and Swait 2019). In contrast to rational choice theory, this model maintains limited working memory and computational capabilities prevent individuals from thoroughly evaluating all options. These scholars argue that when constrained by time and resources, decision-makers—hiring officials included—use heuristics to winnow down choices. To make the number of options manageable, actors deploy heuristic devices or stereotypes to eliminate large swaths of possibilities. Heuristics are “shortcuts,” or simplistic decision rules, which operate “with the goal of making decisions more quickly and frugally […], consistent with the goal of effort reduction” (Gigerenzer and Gaissmaier 2011, 455). The deployment of heuristics consists of “relying on the cue that is perceived as providing the best information” (Krysan and Crowder 2017, 51), thus allowing for problem spaces to be navigated efficiently (Bruch et al. 2016). This theory sheds light on how unclear signals obstruct the selection process.

Contrary to simple heuristics, which allow for decisions to be made frugally and swiftly, unclear signals are complicated and time-consuming to interpret. Deciphering unclear signals is cognitively arduous, which runs counters to screeners’ goal of reducing cognitive efforts in early stages of the decision-making process. The ambiguous meanings embedded in unclear signals leave receivers with uncertainty about senders’ attributes, increase receivers’ likelihood of perceiving the signal as providing poor information, and come in conflict with the receivers’ objective of a streamlined selection process. Generating noisy signals could result in an option being screened out because screeners cannot accurately and efficiently evaluate the quality of the signal sender, as screeners are more likely to base their selection on criteria that they understand well. Signal clarity thus operates as a crucial factor shaping the process through which recipients appraise sender attributes. Under time and resource constraints, risk-averse signal recipients are inclined not to select signal senders with unclear signals, all else being equal.

The Case of Freelancers

Freelancing in the New Economy

Freelancing is inherently precarious for several reasons. First, due to the project-based nature of their employment, freelancers cannot rely on a constant income stream. Compared to full-time employees, who anticipate paychecks with certainty, freelancers operate in continuous cycles of finding projects and negotiating arrangements. Second, freelancers are commonly responsible for their own insurance plans and retirement accounts. Parental and medical leaves are guaranteed to produce income gaps. Third, layoffs or changes in personal circumstances could lead to involuntary freelancing careers. Fourth, the inconstant nature of income streams challenges freelancer abilities to obtain loans and accumulate assets (McGrath and Keister 2008). For those reasons, a substantial percentage of independent contractors wish to embrace an organizational career. The Freelancers Union reports that the difficulty of finding more projects was considered “somewhat” or “very concerning” by 68 percent of surveyed freelancers, and unpredictable income was considered the same by 76 percent (Berland 2015, 35). Fieldwork on independent contractors confirms this insight: “Anyone who has ever tried his or her hand at contracting knows […] that to close a deal, you first have to find one and that finding one is no trivial task. Doing so regularly is even harder” (Barley and Kunda 2006, 98). In order to do transition to full-time positions, freelancers must face the hiring process. The next section explores how employers might evaluate signals associated with freelancing histories.

Signal Clarity and the Labor Market Consequences of Freelancing

This section uses joint insights from signaling theory, decision theory, and the “ideal worker” perspective (Kelly et al. 2010) to discuss how evaluators perceive signals of competence and commitment from applicants with freelancing histories. Regarding competence, freelancing could signal an entrepreneurial spirit. Because freelancers run their own businesses, employers might assume that freelancers have strong work ethics, are passionate about work, and are knowledgeable about small company operations. If freelancers can consistently obtain new projects, they also likely are skilled at pitching, selling, and negotiating―skills on which employers put a premium.

However, a history of freelancing embeds degrees of ambiguity. Unlike full-time workers, who are vetted and trained by full-time employers, freelancers are more loosely attached to formal organizational processes. The source of legitimacy for full-time workers comes from their employer. Contrastingly, as organizationally detached labor market actors, freelancers rely on “personal branding” to market themselves (Vallas and Cummins 2015). Since freelancers may have worked for different organizations without being fully affiliated with any, employers might find it challenging to track down specific clients that hired freelancers and gain insights on the quality of tasks performed. This factor could potentially disadvantage freelancers—who are more loosely attached to formal organizational processes than full-timers and who have been vetted, trained, and evaluated by employers. In the labor market, signals gain clarity if they imply certification or validation from credible parties. When evaluators lack access to clear signals, they could predict signalers’ capabilities by examining how other market actors evaluated the candidate in the past (Sanders and Boivie 2004). Beyond the labor market, Bruch and Feinberg (2017, 217) noted that individuals’ decisions are influenced by the information about their peers’ behavior. By this logic, full-time candidates generate clearer signals of competence because these signals have been externally validated by their previous employers. Comparatively, the detachment from credible employers might obscure freelancers’ legitimacy by excluding them from employer-provided training, evaluation, and endorsement. Certain degrees of uncertainty and unverifiability about freelancing tasks could result in employers having doubts about how updated a freelancer’s skills are. Freelancers can thus be screened out, not because they lack skills but because the signals associated with their skillfulness are unclear.

Employers may also receive unclear signals about freelancer commitment. Positive evaluators could think the dissatisfying aspects of contract work make freelancers grateful for and committed to full-time opportunities. On the flip side, some freelancers previously held full-time jobs. One can become a freelancer due to dislike of office politics and managerial incompetence (see Barley and Kunda 2006). Freelance jobseekers are likely to re-encounter these problems once they return to organizations. Freelancers’ fluid movement between organizations can cause employers to see them as undesirable job-hoppers (Bills 1990). Hiring officials might also wonder if job-seeking contractors are finding a “parking spot” and would leave once their situations change. In sum, signal clarity might condition the ways in which employers evaluate freelancers’ competence and commitment and ultimately decide whether or not to hire them. To date, there is little empirical evidence about the labor market consequences of freelancing or about the mechanisms that underlie such consequences. The two interrelated studies presented below shed light on these dynamics.

Study 1: The Field Experiment

The Study

This study used a unique field experiment that involved submitting nearly 12,000 applications to 6,000 real job openings in 50 metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) between January and March 2017. This research used a national online job board. Following existing audit studies (Gaddis 2014; Pedulla 2016), I submitted fictitious applications for three different job types: marketing, sales, and administrative assistant. I chose these job types because freelancing is relatively common therein. Freelancers can operate as independent marketing consultants, self-employed sales agents, and independent or virtual administrative assistants. It is reasonable to assume that hiring officers can realistically expect to receive applications from workers with freelancing experience in these fields.

I selected the 50 largest MSAs based on the 2016 Census population estimates.3 I used a VBA code to obtain the list of all relevant job openings within 25 miles of the MSA. I eliminated all jobs that were entry-level or non-full-time and required the applicant to apply from the employer’s site instead of directly from the job board’s interface and randomized the order of the remaining jobs in the list. I then created a series of different candidate profiles with three employment histories (full-time, freelancing, and unemployed) and four races/ethnicities (White, Asian, Latino, and Black). Simultaneously varying these two axes yielded 12 profiles. I randomly selected 2 from these 12 profiles to send to each of the 6,000 job-city combinations. I randomly selected the profile of the first candidate. I made sure the second candidate of the pair did not overlap the first in either of the attributes. The online supplementary material for Appendix A shows an example of the treatment used.4

As for applicant educational history, I split the MSAs into four large Census regions: Northeast, Midwest, South, and West. I selected two large public degree-granting institutions of comparable prestige from each region. No pair of schools chosen differed by a margin larger than two in their 2016 U.S. News ranking.

I constructed the resumes based on a publicly available bank of real resumes. After obtaining a college degree, each applicant held a first and a second job. I experimentally manipulated the third professional block in the resumes, which lasted 20 months for all applicants. A third of the applicants were unemployed, another third transitioned to freelancing, and the last third took full-time positions.

I created home addresses, local phone numbers, and email addresses for all applicants. I relied on RentJungle.com rental data to select apartment complexes with monthly rents equivalent to the MSA’s average for all candidates. As much as possible, I kept addresses within the same neighborhoods. The addresses included real apartment buildings, but the apartment numbers were fictitious. I purchased eight unique phone numbers for each race–gender combination for each city. After creating the resumes, I submitted the applications. After sending the first application, I established a 24-hour waiting period before sending the second one. I allowed employers 15 weeks to respond to applicants, by either email or phone. Data collection is finished after I recorded the number of callbacks and the deleted employers’ identifying information. A total of 11,871 applications were actually sent out, instead of 12,000 as originally planned. This 1.01 percent attrition rate resulted from employers removing the job listings after I submitted the first application, but before I sent the second one.

Results

Descriptive Results

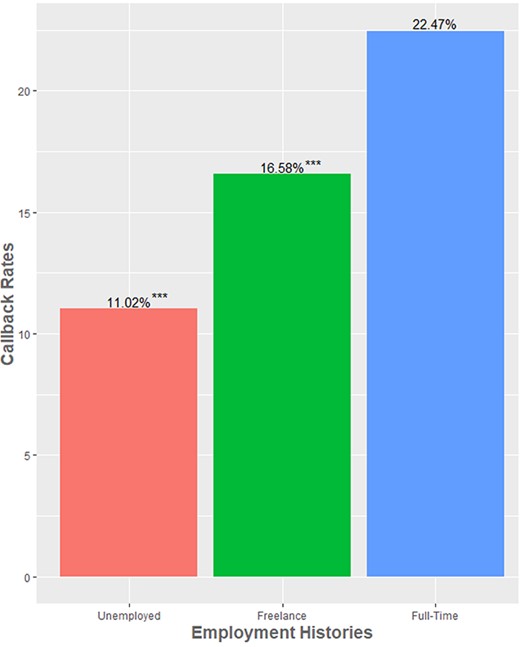

Figure 1 displays the callback rates for each employment history category. For consistency, I used two-tailed two-sample tests in all comparisons. The overall callback rate was 16.68 percent. Freelancers received a 16.58 percent callback rate. This rate was 35.5 percent lower than the callback rates that full-timers received; the difference was statistically significant at the .001 level. Similarly, freelancer callback rates were significantly higher than rates for long-term unemployed workers (16.58 percent vs. 11.02 percent, p < .001). These results indicate that freelancing occupies a middling position between full-time work and long-term unemployment. Employers seem to prefer freelancers over unemployed jobseekers, suggesting that a history of freelancing is not as damaging to workers’ prospects as remaining jobless. At the same time, hiring decision-makers demonstrate a preference for full-time candidates over otherwise comparable freelancing ones.

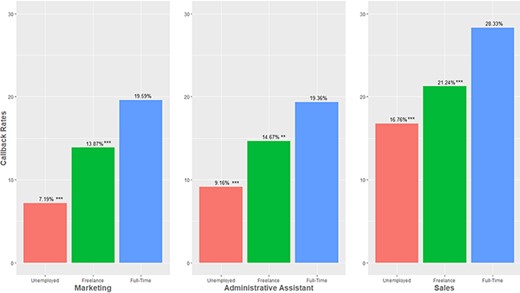

Figure 2 shows several callback rates for different employment histories broken down by job type. Sales are the least selective jobs, marketing the most, and administrative assistant in between. The overall pattern is consistent with the one shown in figure 1: in all three job types, freelancers received significantly lower callback rates than full-time applicants. The differences are statistically significant at the .001 level for marketing and sales jobs and at the .01 level for administrative assistant jobs. Similarly, unemployed applicants are called back at a much lower rate than their freelancing counterparts are. The differences are significant at the .01 level in all three job types analyzed. These results suggest that overall, a history of freelancing is not as convincing to employers as one of full-time employment. However, employers seem to find workers with freelancing work experience more desirable than those who are unemployed.

Callback rates for different employment histories by job types.

Regression Results

Table 1 displays a series of regression models with race, employment history, and job type predicting the likelihood of an applicant getting a callback. Models 1 and 2 are binary logistic regression models with standard errors clustered by job openings. Model 2 includes MSA-fixed effects, while model 1 does not. Models 3 and 4 are all generalized hierarchical linear models without city-level predictors, but they have different nesting structures. Model 3 is a two-level model with applicants nested in 50 cities, whereas model 4 is a three-level model with applicants nested in 150 job-cities, which are in turn nested in 50 cities. Model 5 is a conditional logit model, which is appropriate since the experiment used matched pairs of job candidates. Each job opening is modeled as a stratum in model 5. The results are consistent across all models. In terms of penalties for not holding full-time jobs, model 2, for example, affirms a negative mobility effect associated with a history of freelancing. Ceteris paribus, the odds of obtaining a callback decrease by 31 percent when a jobseeker goes from being a full-timer to a freelancer. Similarly, all else being equal, compared to maintaining full-time employment, 20 months of unemployment decrease the odds of a jobseeker getting a callback by 58 percent. Despite lagging behind workers with seamless employment histories, freelancers are regularly selected ahead of their unemployed counterparts.

Logistic Regression, Generalized Linear Mixed Model, and Conditional Logistic Regression Results of Employment History Predicting the Likelihood of Getting a Callback

| . | Dependent variable: callback vs. no callback . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Logistic regression . | Generalized linear mixed effect . | Conditional logit . | ||

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . |

| Employment history (ref = full-time) | |||||

| Freelance | −.3733*** | −.3753*** | −.3743*** | −.3808*** | −.7320*** |

| (.0500) | (.0505) | (.0582) | (.0584) | (.1107) | |

| Unemployed | −.8580*** | −.8684*** | −.8643*** | −.8686*** | −1.4833*** |

| (.0568) | (.0575) | (.0643) | (.0643) | (.1209) | |

| Race/ethnicity (ref = White) | |||||

| Latino | −.4005*** | −.4044*** | −.4030*** | −.4091*** | −.6748*** |

| (.0628) | (.0632) | (.0681) | (.0683) | (.1374) | |

| Asian | −.2586*** | −.2655*** | −.2632*** | −.2667*** | −.5569*** |

| (.0597) | (.0603) | (.0666) | (.0667) | (.1351) | |

| Black | −.8322*** | −.8384*** | −.8366*** | −.8398*** | −1.4274*** |

| (.0689) | (.0694) | (.0748) | (.0749) | (.1514) | |

| Job type (ref = sales) | |||||

| Admin | −.5378*** | −.5251*** | −.5305*** | — | — |

| (.0729) | (.0733) | (.0604) | |||

| Marketing | −.6120*** | −.6091*** | −.6101*** | — | — |

| (.0735) | (.0744) | (.0615) | |||

| Constant | −.5370*** | −1.2483*** | −.5497*** | −.9356*** | — |

| (.0638) | (.2314) | (.0698) | (.0639) | — | |

| MSA-fixed effects | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| AIC | 10267.5 | 10238.5 | 10239.5 | 10285.1 | 936.0423 |

| BIC | 10326.5 | 10569.3 | 10305.9 | 10344.2 | 969.5874 |

| N | 11,870 | 11,870 | 11,871 | 11,871 | 11,870 |

| . | Dependent variable: callback vs. no callback . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Logistic regression . | Generalized linear mixed effect . | Conditional logit . | ||

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . |

| Employment history (ref = full-time) | |||||

| Freelance | −.3733*** | −.3753*** | −.3743*** | −.3808*** | −.7320*** |

| (.0500) | (.0505) | (.0582) | (.0584) | (.1107) | |

| Unemployed | −.8580*** | −.8684*** | −.8643*** | −.8686*** | −1.4833*** |

| (.0568) | (.0575) | (.0643) | (.0643) | (.1209) | |

| Race/ethnicity (ref = White) | |||||

| Latino | −.4005*** | −.4044*** | −.4030*** | −.4091*** | −.6748*** |

| (.0628) | (.0632) | (.0681) | (.0683) | (.1374) | |

| Asian | −.2586*** | −.2655*** | −.2632*** | −.2667*** | −.5569*** |

| (.0597) | (.0603) | (.0666) | (.0667) | (.1351) | |

| Black | −.8322*** | −.8384*** | −.8366*** | −.8398*** | −1.4274*** |

| (.0689) | (.0694) | (.0748) | (.0749) | (.1514) | |

| Job type (ref = sales) | |||||

| Admin | −.5378*** | −.5251*** | −.5305*** | — | — |

| (.0729) | (.0733) | (.0604) | |||

| Marketing | −.6120*** | −.6091*** | −.6101*** | — | — |

| (.0735) | (.0744) | (.0615) | |||

| Constant | −.5370*** | −1.2483*** | −.5497*** | −.9356*** | — |

| (.0638) | (.2314) | (.0698) | (.0639) | — | |

| MSA-fixed effects | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| AIC | 10267.5 | 10238.5 | 10239.5 | 10285.1 | 936.0423 |

| BIC | 10326.5 | 10569.3 | 10305.9 | 10344.2 | 969.5874 |

| N | 11,870 | 11,870 | 11,871 | 11,871 | 11,870 |

Note: Clustered robust standard errors at the job-opening level in parentheses in models (1) and (2). Job application number included (not shown) in model (5). Log odds presented.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001 (two-tailed tests).

Logistic Regression, Generalized Linear Mixed Model, and Conditional Logistic Regression Results of Employment History Predicting the Likelihood of Getting a Callback

| . | Dependent variable: callback vs. no callback . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Logistic regression . | Generalized linear mixed effect . | Conditional logit . | ||

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . |

| Employment history (ref = full-time) | |||||

| Freelance | −.3733*** | −.3753*** | −.3743*** | −.3808*** | −.7320*** |

| (.0500) | (.0505) | (.0582) | (.0584) | (.1107) | |

| Unemployed | −.8580*** | −.8684*** | −.8643*** | −.8686*** | −1.4833*** |

| (.0568) | (.0575) | (.0643) | (.0643) | (.1209) | |

| Race/ethnicity (ref = White) | |||||

| Latino | −.4005*** | −.4044*** | −.4030*** | −.4091*** | −.6748*** |

| (.0628) | (.0632) | (.0681) | (.0683) | (.1374) | |

| Asian | −.2586*** | −.2655*** | −.2632*** | −.2667*** | −.5569*** |

| (.0597) | (.0603) | (.0666) | (.0667) | (.1351) | |

| Black | −.8322*** | −.8384*** | −.8366*** | −.8398*** | −1.4274*** |

| (.0689) | (.0694) | (.0748) | (.0749) | (.1514) | |

| Job type (ref = sales) | |||||

| Admin | −.5378*** | −.5251*** | −.5305*** | — | — |

| (.0729) | (.0733) | (.0604) | |||

| Marketing | −.6120*** | −.6091*** | −.6101*** | — | — |

| (.0735) | (.0744) | (.0615) | |||

| Constant | −.5370*** | −1.2483*** | −.5497*** | −.9356*** | — |

| (.0638) | (.2314) | (.0698) | (.0639) | — | |

| MSA-fixed effects | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| AIC | 10267.5 | 10238.5 | 10239.5 | 10285.1 | 936.0423 |

| BIC | 10326.5 | 10569.3 | 10305.9 | 10344.2 | 969.5874 |

| N | 11,870 | 11,870 | 11,871 | 11,871 | 11,870 |

| . | Dependent variable: callback vs. no callback . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Logistic regression . | Generalized linear mixed effect . | Conditional logit . | ||

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . |

| Employment history (ref = full-time) | |||||

| Freelance | −.3733*** | −.3753*** | −.3743*** | −.3808*** | −.7320*** |

| (.0500) | (.0505) | (.0582) | (.0584) | (.1107) | |

| Unemployed | −.8580*** | −.8684*** | −.8643*** | −.8686*** | −1.4833*** |

| (.0568) | (.0575) | (.0643) | (.0643) | (.1209) | |

| Race/ethnicity (ref = White) | |||||

| Latino | −.4005*** | −.4044*** | −.4030*** | −.4091*** | −.6748*** |

| (.0628) | (.0632) | (.0681) | (.0683) | (.1374) | |

| Asian | −.2586*** | −.2655*** | −.2632*** | −.2667*** | −.5569*** |

| (.0597) | (.0603) | (.0666) | (.0667) | (.1351) | |

| Black | −.8322*** | −.8384*** | −.8366*** | −.8398*** | −1.4274*** |

| (.0689) | (.0694) | (.0748) | (.0749) | (.1514) | |

| Job type (ref = sales) | |||||

| Admin | −.5378*** | −.5251*** | −.5305*** | — | — |

| (.0729) | (.0733) | (.0604) | |||

| Marketing | −.6120*** | −.6091*** | −.6101*** | — | — |

| (.0735) | (.0744) | (.0615) | |||

| Constant | −.5370*** | −1.2483*** | −.5497*** | −.9356*** | — |

| (.0638) | (.2314) | (.0698) | (.0639) | — | |

| MSA-fixed effects | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| AIC | 10267.5 | 10238.5 | 10239.5 | 10285.1 | 936.0423 |

| BIC | 10326.5 | 10569.3 | 10305.9 | 10344.2 | 969.5874 |

| N | 11,870 | 11,870 | 11,871 | 11,871 | 11,870 |

Note: Clustered robust standard errors at the job-opening level in parentheses in models (1) and (2). Job application number included (not shown) in model (5). Log odds presented.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001 (two-tailed tests).

Altogether, the field experiment offers robust evidence of the labor market disadvantage that freelancers face relative to otherwise similar full-time applicants in transitioning back to regular employment. It is important to note that the field experiment took place in early 2017, when the national unemployment rate declined to its lowest level in almost a decade. It is thus possible that the callback rates were inflated and the results underestimated the impact of employment history on callback likelihood.

Study 2: Interviews

The Study

While the field experiment finds robust causal effects of freelancing on callbacks, it does not elucidate the mechanisms that might drive these findings. To gain insight into these mechanisms, I conducted 42 semi-structured in-depth interviews with individuals involved with the hiring process in their organizations. Such interviews help reveal employers’ perceptions of candidates, which may shape their subsequent hiring behaviors (Moss and Tilly 2001). To my knowledge, with the exception of Rivera and Tilcsik (2016), this is the first study combining a field experimental data with qualitative interviews to unpack the black box of hiring discrimination. I used advertisements on multiple social networking sites to identify potential respondents. I used university alumni directories and multi-site referral chains to identify hiring officers following past research with hiring decision-makers (see Rivera 2012; Rivera and Tilcsik 2016).5 Interviews were conducted in person or by phone and recorded; they lasted between 30 and 90 minutes. The online supplementary material for Appendix B shows information about interview respondents. I use pseudonyms for all respondents, and slightly altered some of their titles, to protect their identities. All data were coded using NVivo.

Results

Competence

Upsides of freelancing histories

Some employers compliment freelancers’ skills and see upsides in the diversity of their experience. Ashley explained: “What is positive about freelancers is that they’re agile. They’ve had more of a diverse background because they’re not tied down to a place, they have room for creativity.” Other employers noted that freelancers are “creative,” are “forward-thinking,” and have “a broad horizon” and that “exposure to different projects and industries” equips freelancers with “a different way of looking at issues and finding solutions” and “a holistic view of their job responsibilities.” Evaluators appreciate how freelancers are well-versed at different aspects of running a small business. Stacey said: “When running one’s own business, you’re your own security worker, accountant, and sales. You have to be the mastermind behind all these departments. That’s a unique skill-set that I look for when I hire.” The ability to operate an independent business suggests to employers that freelancers can “manage their time well” and “juggle multiple projects at once.” Some respondents admire freelancers’ entrepreneurial spirit; several employers described freelancers as “self-starters,” workers who are “passionate for work,” and “ambitious.” For instance, Johanna expressed an impression of freelancers that was very common among the employers interviewed:

“Freelancing can honestly be a positive thing. […] It requires a certain amount of confidence and drive to be able to be your own employer and count on yourself for your income, and in America your health care. […] [So a freelancer is] someone who’s very enthusiastic, confident in themselves, and willing to take risks.[…] Taking ownership of yourself, your development, and your career, that’s just so important.”

Employers’ reservations

Although some employers consider freelancers as energetic entrepreneurs, approximately two-thirds of respondents are skeptical or uncomfortable with how unclear multiple aspects of the freelancing experience are. In a few cases, evaluators fear that freelancers are seeking full-time employment because their self-employed business failed, which sends signals of poor candidate quality. Brent expressed his concerns: “If they’re looking for a job, that means that their business may or may not be failing.” He explained how such perceptions directly affect hiring outcomes: he might “move them along [to the next stage], […] but it never ends well for the candidate.”

Like Brent, Craig had questions for freelancing candidates: “Why do you want a full-time position if you have your own practice? […] What was your workload like? Who can we contact for references […] We need to verify income sometimes.” According to him, this information is “a lot harder to get with freelancers.” Tara voiced a similar sentiment: “We check references and […] reach out to previous employers to get a better gauge of [candidates’] work. It’s a bit more difficult to do that when they’re freelancers.” These quotes suggest that the inability to verify signals challenges employers’ efforts to interpret freelancer quality. Vince echoed other employers’ sentiments: “Freelancers are their own brand,” and they “don’t have a brand behind them, [one that would] boost their credibility […] It is harder to verify their background if you don’t have an organization to check it against.”

Additionally, some employers are uncertain about the training and evaluations that freelancers received. Gwen described questions she might have of an applicant who freelanced:

“The extent of what they know[…] how proficient they are […], sometimes it might be a little difficult to say. […] When they’ve worked at a company and we’ve hired from that company before we can say: “Oh, we know that [Firm] does a great job at training people with this program.” So when you get a freelancer, it’s a little difficult because we wonder how you train and develop yourself, what do you do to measure your proficiency as opposed to a big company that has training programs.”

Mandy also has reservations about the lack of clarity associated with freelancers’ work because the tasks these candidates performed were not organizationally appraised. She asked: “If they’re freelancing, they’re not going through performance evaluations from a company. Are they really learning and understanding how to grow?” Other hiring officials worried that freelancers are seeking regular employment because their clients did not offer them full-time positions. Susan explained: “I would question: ‘Was there an opportunity for that freelance role to turn full-time?’ The reality is that if you’re really good, even if you’re in a freelance role, sometimes the employer will give you a full-time offer.”

Given the uncertainty embedded in the recruitment process, hiring officers can reduce ambiguity by analyzing how other firms evaluated the candidate. Candidates’ signal clarity and credibility can improve if other firms hired them, trained them, and vouched for them. Freelance work has inherent features that make this evaluation difficult. Freelancers are looking for jobs, so employers might wonder if the lack of full-time employment signifies poor quality. Freelancers may not have undergone employer-provided training, so evaluators face difficulties judging their skill levels. Compared to full-time applicants whose credibility can be enhanced by their association with a reputable employer, freelancing applicants are more organizationally detached and engage in “personal branding” (Vallas and Cummins 2015). As the quote by Vince suggests, hiring officers find self-endorsed signals less credible than organizationally endorsed ones. Altogether, employers seem to struggle with interpreting signals of capabilities because freelancers lack attachment to previous credible employers. This finding supports the perspective that employers face difficulty evaluating freelancers’ skills partly because of the ambiguities associated with this employment arrangement. But how does this factor differentiate full-time applicants from freelancing candidates?

Hiring officials interpret competence signals of full-timers with ease. Tim explained that full-time candidates “performed at a company where they were held accountable for their performances. They had to deliver to stakeholders.” This perception resulted in him saying: “I would actually prefer the candidate from a well-known company or something I’m familiar with, as opposed to going with an unknown freelancer.” Organizational training and performance evaluation are common in modern organizations (Castilla 2008). Hiring officials are accustomed to interpreting signals of competence from full-time workers because these candidates had presumably been hired, trained, and systematically appraised by credible organizations. Employers frequently stated that “the ideal candidate is having another job already.” The full-time employer thus operates as a source of legitimacy and a benchmark against which candidates’ skills can be evaluated. This factor plays a crucial role in the process through which evaluators compare freelancing candidates to their full-time counterparts. Tom, a hiring official at a tech firm, explained his preference for full-timers as follows:

“I would obviously gravitate more towards the full-time candidate merely because I’m used to seeing a chain of jobs together. […] It’s just more data for me to consider. I usually gravitate more towards data analyzing trends and metrics, and with more jobs, I can place more plot points […] For the freelancer, it’s hard to say. They could have had a chain of jobs and suddenly stopped. That’s a larger gap of data, […], it’s more of a mystery.”

When asked how a freelancing candidate compares to a full-time one, Earl also captures this process:

“Let’s say that all other things are equal, […] I would look more favorably on the candidates who had been in a full-time position. 100 percent. I’d probably be able to better understand what they were doing. […] It’s more clear-cut. Just think about the efficiency of the process. I have to look through hundreds of resumes. It’s easier for me to say, ‘Oh, you’ve been at this company for two years and you got a promotion? That tells me […] you have some progressive experience. […] You must have done your job well and somebody said, “Yes, you should get more responsibility.”’”

He described his evaluation of a freelancer’s profile as follows:

“I am intrinsically a skeptic while trying to be an optimist […] I’m very cautious when someone says that they were the CEO of their own consulting firm. I want to know types of clients, types of works, deadlines, responsibilities, outcomes, KPI metrics that are relevant. If […] the answers are sketchy, that will be a knock against them. Sometimes I can develop a story in my head that might be compelling enough to talk to the freelancer about why he or she wants a full-time role. […] But that’s something I have to dig out of somebody. Again, the common thread is that I can evaluate with less information someone who has been in the full-time role and has more of a traditional background. I have a lot more question marks for someone who’s coming from a freelancing role.” [emphasis mine]

This quote illustrates how clarity in competence signals operates as a key mechanism separating employers’ evaluations of full-time candidates from freelancers. Employers opine that full-time work experience emits clearer competence signals because the candidate has possibly been trained and evaluated by full-time employers. These factors make full-time workers’ resumes more “understandable” and “clear-cut,” partly because employers are “used to seeing” these employment histories and can evaluate them “with less information.” Earl’s emphasis on the “efficiency” of the process in which he has to “look through hundreds of resumes” captures the use of heuristics to winnow down choice sets among decision-makers. Tom’s and Earl’s quotes demonstrate how the “large gaps of data,” the “mysteries,” and the “question marks” surrounding a freelancer’s resume make it cognitively taxing for them to evaluate these candidates (see Bruch and Feinberg 2017). These results suggest that the lack of affiliation with an organization and the detachment from the legitimacy that organizational training and evaluation provide contribute to unclear freelancer competence signals, which consequently disadvantages this group at hiring.

Commitment

More than half of the hiring officials interviewed cite the inability to commit to full-time work as a possible deterrent to hiring freelancers. Why might employers prioritize signals of commitment? Several respondents emphasize how a hiring decision imposes a substantial cost, in terms of finance and effort, on the hiring firm. Carolyn explained: “Bringing somebody on board is a lot of work. It’s a lot of training, development, how-to […]. It is a big commitment, it’s something that you want to be worthwhile.” She explained how, even after accounting for skills, perceivably uncommitted freelancers can be seen as incongruent with a firm prioritizing commitment and retention:

“Some hiring managers are not fans of the frequent turnaround in jobs. That can be a hurdle sometimes even with good candidates […] Some just don’t like the fact that they change jobs frequently, even though the jobs were freelance […] Changing jobs frequently does give managers the thought that maybe they are noncommittal.”

Natalie considered the attrition risk as a major financial concern: “Having hired someone and replacing them, the cost is so extreme. You put the training in, only so that six months later, they decided to go back to freelancing. The money that we put into it and lost, that’s the biggest concern (emphasis mine) for my HR department.” Evaluators repeatedly emphasized that they look for “longevity”; they want candidates that are “all in” and “thinking long-term.” Meanwhile, some evaluators perceive that freelancers are used to working on short-term contracts and could be motivated by short-term goals, in contrast with employers’ visions. Jill explained how she questioned freelancers’ motives when going full-time:

“I would be concerned as to what their goals are. Are they looking for a short-term one? Maybe they aren’t bringing enough money in […] doing whatever they’re doing independently, so they’ll just get some extra cash […] to hold them off for a few months [before] they go back to freelancing.”

She explained her experience with hiring a freelancer for a full-time position, who quitted shortly thereafter. She identified the incongruence between the firm’s long-term vision and the candidate’s short-term goal as the factor resulting in freelancers’ poor commitment:

“So we’ve hired people that were freelancing […] Only a few months down the road, they left. [In the exit interviews], they tell me that they want to go back to doing what they did before. […] I think that it has to do with that short-term/long-term goals [emphasis mine]. They worked a few months, they got the money they need, and now they’re back [to freelancing]”

Miranda pinpointed commitment as a direct factor resulting in a full-time candidate getting an interview over a freelancing one:

“I can definitely verify [emphasis mine] that [HR managers] will call and speak to the person that has the recent full-time permanent experience over calling the independent consultant. It really comes down to the commitment. That person is coming from an environment where they probably have to work 9 to 5, Monday to Friday, couldn’t work from home frequently.”

Instead of sending an unclear signal, freelancing as an employment history seems to send a clear negative commitment signal to many employers. Evaluators see freelancers as potential attrition risks who might not commit to working full-time and adapting to their firms’ organizational structures and who might revert to the freelancing lifestyle after absorbing their firms’ training and development. In contrast, full-timers are perceived as more committed, stable, and adjustable to existing organizational structures, which could result in lower possibilities for turnover.

Discussion and Conclusion

Despite the growth of freelancing, prior scholarship offers little systematic evidence on penalties that freelancers might face in reintegrating into the full-time workforce. This paper addresses this gap and demonstrates that freelancers are disadvantaged relative to candidates with histories of full-time employment at the hiring stage. It also elucidates the mechanisms that might account for this penalty. Drawing on the concept of “signal clarity,” I propose a model to theorize labor market opportunity structures associated with freelancing. I argue that signal clarity conditions the process by which employers appraise candidates’ qualities, which in turn shapes their decision regarding jobseekers’ candidacies. I illustrate this model using the case of freelancers, since freelancing and the tasks performed in this mode of employment straddle between theoretically delineated categories of “primary” and “secondary” labor markets, have features of both “good” and “bad” jobs, and embed inherent ambiguity around their meaning and categorization.

In the first study, I analyzed data from an original large-scale field experiment to derive causal estimates of the effect of freelancing on labor market outcomes. I found that the odds of getting a callback decreased by about 30 percent when a jobseeker went from being a full-time candidate to a freelancing one. In the second study, interviews with employers reveal two mechanisms behind that observed gap. First, freelancing sends decidedly unclear competence signals. While employers appreciate freelancing candidates’ diverse skill-set, they were hesitant to move these candidacies forward partly because of the ambiguities around their skills. Employers repeatedly expressed difficulty in interpreting and verifying signals of freelancers’ performance capabilities. In other words, freelancers are disadvantaged not because they lack competence but because the signals associated with their competence are unclear. In contrast, full-time candidates’ skills send clear signals because these candidates were presumably trained, evaluated, and backed by credible organizations. Second, the commitment signal associated with freelancing work history is less unclear and negative. Evaluators had doubts about freelancers’ job-hopping patterns and routinely expressed worries over freelancers’ perceived inability to commit to working full-time and to their organizations once hired. This study illustrates how signal clarity can operate in varying extents: a freelancing history can send an unclear signal of competence and a relatively clear and negative signal of commitment.

This study has several limitations. First, it only explores the initial stage of the job application process and cannot speak to the dynamics of job interviews, salary negotiations, and subsequent career advancements. Second, due to the small number of industries covered, I am unable to examine potentially different meanings of freelancing across industries. It is plausible that among software engineers, where freelancing is somewhat normative, freelancers may be viewed as equally desirable as their comparable full-time counterparts. It is possible that freelancing could generate different meanings across different industries, and the findings of this study need to be interpreted with this limitation in mind. Third, given the dearth of survey data on freelancers, it is unclear whether the length of the freelancing period (20 months) in the experiment is representative of this population—a common challenge among field experiments (see Heckman 1998). This limitation is mitigated by the consistency with which hiring officials elaborated on their perceptions of freelancing job applicants without prompts about the length of jobseekers’ freelancing experience in the qualitative interviews. Fourth, the results do not extend to lower-skilled freelancers such as rideshare drivers and handypersons, groups that are likely very different from those studied here.

These limitations notwithstanding, this study generates important findings and implications. This research reveals a scarring effect of freelancing: compared to full-time workers, freelancers face substantial roadblocks in transitioning back to standard employment. Given the debate between labor market integrationists (Giesecke and Groß 2003) and segmentationists (Doeringer and Piore 1985), this paper yields findings that support the latter. Since segmentation theory predicts a stark demarcation between the primary and secondary sectors, the fact that freelancing work has characteristics of both sectors could make one question the applicability of the theory to explain mobility structures for this population. This paper reports that even when freelancing work has many characteristics of employment arrangements in the primary sector, employers are ambivalent about freelancers, consider them a tier below full-time workers, and relegate them to the secondary sector. This result could suggest that segmented labor market theory is even more general than it is given credit for. This theory can be generalized to account for mobility structures associated with nonstandard jobs, even when those jobs require a high level of training, are well-compensated, and afford workers with relatively high autonomy. This finding indicates that the mode of employment―rather than the skills, compensation, and autonomy associated with it―seems to be the decisive factor driving worker advancement opportunity.

This paper argued and demonstrated that freelance work is different from other working arrangements that deviate from standard work norms. The existing work argued that compared to full-time workers, workers whose career paths deviate from traditional modes of employment fared worse in the labor market because employers evaluate them as less competent and lower-skilled (Hirsch 2005; Pedulla 2016). Weisshaar (2018) reported that opt-out applicants are rated as less capable compared to full-time workers. This study’s results presented a different way in which freelancers are disadvantaged. I showed that at the hiring stage, freelancers face adverse outcomes relative to full-time workers not because they are perceived as less competent but because the signals associated with their competence are unclear. In the case of freelancers, stratified outcomes do not stem from the lack of competence like it does for other groups of nonstandard workers. The disadvantage instead originates from the lack of clarity associated with their employment history. What are some tactics that freelancers can pursue to alleviate unclear competence signals? They could potentially expand their “personal branding” (Vallas and Christin 2018) efforts to send personally endorsed signals of their professionalism and skills to appease employers’ reservations. These efforts are increasingly necessary, even normative, in social contexts where precarity is progressively professionalized (Besbris and Petre 2019). It remains to be seen if this strategy is effective, since gatekeepers in this study repeatedly raised hesitations about freelancers’ lack of organizationally endorsed signals. Alternatively, freelancers could seek to obtain additional certificates and credentials to reduce signal uncertainty. Future studies should explore the role of licensure and credentialing in enhancing signal clarity, thereby improving career chances for freelancers in occupations where formal certification processes are normative.

Although freelancers underperform full-timers in terms of callback rates, the field experiment results also show that freelancers are consistently selected ahead of unemployed workers. Among the studies comparing labor market outcomes between unemployed and nonstandard workers, Yu (2012) showed that accepting a contingent job delayed jobseekers’ transition to standard employment more than remaining unemployed. Pedulla (2016) found that part-time work, skill underutilization, and temporary agency employment do not result in callback rates higher than those for unemployed jobseekers. In contrast, when analyzing another segment of the contingent workforce, this paper found that freelancing applicants significantly outperform their unemployed counterparts. Such findings could speak to the premium that employers put on workers’ agency and entrepreneurial spirit and suggest that freelancers are grouped in a separate category from other types of nonstandard workers. Despite the lack of clarity associated with competence signals, employers value freelancers more than part-time and temp workers. This finding supports the view that the contingent workforce is heterogeneous and should be studied using disaggregated data. Fully embracing this heterogeneity has another important implication for labor market segmentation theory. These insights could push dual labor market theory toward a more nuanced theory of a multi-tiered secondary labor market, where employers in the primary workforce evaluate different segments of the nonstandard workforce through different lenses and mechanisms.

This paper argues for the clarity contingency of signals. Although existing sociological models suggest that employers evaluate different status characteristics by evaluating how such characteristics send signals of candidate quality, scholars have not paid sufficient attention to the variation in clarity of those signals. While incorporating signal clarity complicates existing understandings of employers’ evaluation, more parsimonious accounts cannot fully explain the process through which gatekeepers arrive at attributions. The findings presented here highlight how signal clarity complicates the ways in which signals are appraised, and this complication constitutes a missing aspect of understanding how cognitive processes contribute to generating stratified outcomes in society more broadly. These processes likely extend beyond the labor market. For instance, while evaluating applications for college admissions, admission committees might have a harder time processing profiles of international students relative to domestic ones. International candidates might be highly competent applicants, but some aspects of their applications could send unclear signals. Compared to domestic candidates, international students come from a dissimilar educational system. The class ranks of students might embed different meanings, the grade point averages operate on different scales, and reputations of their high schools are not as easily interpretable. These factors likely disadvantage international students when admission officers choose between thousands of profiles. In another setting, Bruch et al. (2016) reported that failing to upload a photo can result in a profile being 20 times less likely to be browsed in the context of online dating. Signal clarity potentially serves as an operating mechanism here. By not providing a picture, the user generates decidedly unclear signals about his/her appearance. Online dating is an uncertain process with thousands of potential partners, and adding more uncertainty by sending unclear signals likely worsens the odds of being browsed and written to.

This research also opens various avenues for future studies. As this study indicates, freelancers face penalties when applying for full-time jobs, but there is little evidence about whether these penalties persist in the workplace once these applicants become employees. Future work is needed to analyze whether the negative externalities associated with a history of freelancing continue to operate once applicants get past the hiring stage. Additionally, future research would do well to theorize how freelancing intersects with other aspects of workers’ identities to generate inequality in the labor market. The consequences of freelancing are unlikely to be consistent across racial/ethnic groups, social classes, gender identities, and immigration histories. In sum, this research contributes to the growing narrative about how gatekeeping behaviors and how dynamics of social stratification operate in a historical moment characterized by a normative restructuring of the nation’s labor queues associated with the shift in employment relations. The insights generated from this study should be of interest not only to sociologist of the labor market but also to scholars and policymakers whose concerns include how stratification are generated, maintained, and reproduced through gatekeeping behaviors across different social arenas.

About the Author

Quan D. Mai is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Rutgers University. He received his Ph.D. in Sociology from Vanderbilt University. His research interests focus on social inequality in the labor markets, nonstandard employment, race, and research methods. His recent publication explores the institutional drivers of work precarity in a cross-national setting. His current research examines how the experience of nonstandard employment shapes various aspects of workers’ lives, including their well-being and labor market prospects.

Footnotes

For the purposes of this paper, I use the terms “independent contractor” and “freelancer” interchangeably.

Studies focusing on freelancers such as Osnowitz (2010) and Barley and Kunda (2006) offer rich insights on the challenges that independent contractors encounter while finding and working on gigs. However, they have less to say about the roadblocks that this population faces in applying for full-time jobs.

From the original list, I replaced Virginia Beach–Norfolk–Newport News and Birmingham–Hoover with Bridgeport–Stamford–Norwalk and Omaha–Council Bluffs because there were not enough job openings in the former two MSAs. I also conducted pilot experiments in St. Louis and Milwaukee–Waukesha–West Allis, so I replaced those two MSAs with Grand Rapids–Wyoming and Rochester.

Employers received resumes from applicants of the same gender. All applicants for sales jobs were men, and all applicants for administrative positions were women. I randomly assigned gender to applicants for marketing jobs. These gender assignments were somewhat consistent with the gender breakdown of the job types. According to the BLS (2016), secretaries and administrative assistant positions are dominated by women (94.6 percent of total employed). Employment of marketing specialists is about evenly split between men and women (55 percent women). Although the gender distribution of sales jobs is even (49 percent women), to keep the number of men and women applicants close to each other, I made sure that sales jobs were men only.

Due to the use of Listserv and advertisement as the main recruitment tools, the response rate is difficult to gauge. The study was advertised primarily on New York- and New Jersey-based websites. This results in a sample of respondents who are concentrated in the Northeast: 28 respondents are from New Jersey, 7 from Pennsylvania, 5 from New York, 1 from Connecticut, and 1 from Virginia. This lack of regional variation likely constitutes a limitation in the sample. Future studies would do well to analyze how perception of nonstandard workers might vary by locations. In terms of subjects covered, all interviews include background information on interviewee, evaluation of freelancer as a separate category, and perception of freelancers relative to full-time and unemployed candidates.