Why the LGBTQ community sidelined police for Pride

NYC Pride will reduce the police presence at this year's annual march.

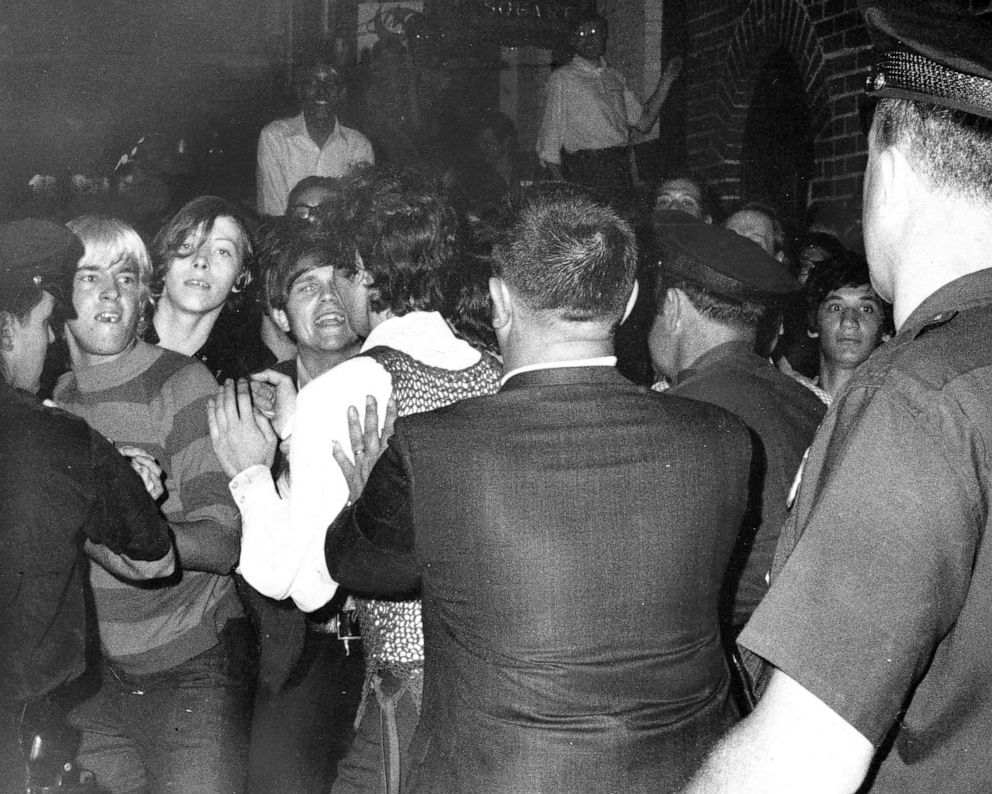

The 1969 police raid of the Stonewall Inn, the famed gay bar in New York City, was no different than many others before it.

For decades, before and after the riots, some law enforcement officers and agencies targeted known LGBTQ-friendly establishments in an effort to shut them down, brutalize patrons, and arrest people who violated the homophobic and transphobic policies of the time, according to the National Park Foundation, an organization that focuses on U.S. history and education.

The Stonewall Uprising of 1969, the culmination of days of protests and clashes with police, was the catalyst for the modern gay rights movement and is what NYC Pride commemorates each year.

However, this June, the annual march will look slightly different -- law enforcement officers won’t be marching in the parade for the first time since about 1981 and there will be a reduced police presence at the organization's events. The ban will remain in place until 2025.

The decision comes as event organizers reckon with the legacy of brutality and abuse against the LGBTQ community by police that they say still continues today.

“Part of the trauma and triggers that our community faces are directly tied to that uniform,” said David A. Correa, the interim executive director at Heritage of Pride, Inc., the nonprofit organization that hosts most of the city’s major Pride events. “To be fully inclusive, you have to make the space safe for everyone. And that sometimes means compromise, and Black and brown people and indigenous people have been compromising for centuries.”

Heritage of Pride said they will be working with a private security team on the day of the parade, Saturday, June 27, to ensure the safety of event participants. They say that a clash between queer liberation demonstrators and the NYPD during Pride month in 2020 also played a role in the decision.

Police asserted that demonstrators were vandalizing NYPD vehicles near Washington Square Park. Viral videos of the confrontation showed officers rush the crowd of protesters, curse at them, and shove and hit them with batons. In some videos, officers seem to be using pepper spray against the crowd.

“Our organization, NYC Pride, was called to the table and asked to take a stance,” Correa said. “Members of our community said, ‘Please stand up for us queer people. We were pepper-sprayed and attacked.’ We took a stance of -- ‘Well, we weren't there. We hope everyone can get along’ ... and it just wasn't enough for folks.”

A spokesman for the NYPD said at the time that it arrested three people involved in the incident. Police said one was charged for graffiti, while two were charged with resisting arrests and assaulting an officer.

“We decided that it was imperative that we put the safety and security of the most marginalized in our communities first and that meant a reduction in policing,” Correa said.

The organizers said that there is still distrust in law enforcement due to ongoing discrimination and harassment against the LGBTQ community. A 2015 report from the UCLA School of Law found that 48% of surveyed LGBT violence survivors who interacted with law enforcement in the U.S. reported police misconduct, including unjustified arrest, use of excessive force and entrapment.

Jason Samuel, of the Gay Officers Action League, a nonprofit LGBTQIA law enforcement advocacy group, said that its members were upset by organizers’ decision to remove law enforcement groups from the lineup. He said he believes that GOAL has served as “a conscience” for the NYPD, of which several of its members serve for and has helped implement sensitivity and awareness training throughout the department.

“While we'd candidly admit there's plenty of work remaining for us to address, it remains, nonetheless, a simple shame to discount what's been accomplished, especially to those officers piloting reform efforts,” Samuel told ABC News. “We'd much rather continue on with bearing witness, maintaining our visibility, and serving a culture of openness, dialogue, and inclusivity.”

In a statement to ABC News, the NYPD said that the department will still be present at the parade in a limited capacity.

“Our annual work to ensure a safe, enjoyable Pride season has been increasingly embraced by its participants,” the statement read. “The idea of officers being excluded is disheartening and runs counter to our shared values of inclusion. That said, we’ll still be there to ensure traffic safety and good order during this huge, complex event.”

Criminalizing the LGBTQ community

Some laws, and many of those who’ve enforced them, have long criminalized the LGBTQ community across the country, and have made even daily activities much harder for the marginalized group.

Laws that prohibited lewdness, vagrancy, and disorderly conduct, like Michigan’s Section 750.338 which still remains in the state penal code, had been used by police to harass queer people when they gathered in public spaces since the 1800s. Law enforcement officers would raid bars and clubs or cruise queer-friendly locales as undercover cops to catch LGBTQ people in the places they felt most comfortable being themselves, according to Terry Beswick, the executive director of the GLBT Historical Society.

“The raids that we know about … just happened to be those few early cases and instances where people fought back,” said Beswick. “It wasn't just a matter of clearing the bar. People would be brutalized and beaten, thrown into jail. Their names would be printed in the newspaper, they would lose their job if they were in the closet, lose their family.”

And sodomy laws, which have roots in some of the earliest laws of the U.S., made same-sex relations or sexual activity illegal, according to Jen Manion, a history professor at Amherst college. Throughout the 1900s, law enforcement had several avenues to pursue against LGBTQ people, via laws against disorderly conduct, indecency, loitering, lewdness, and more.

“There was just a lot of entrapment,” Manion said. “Undercover flirting, engaging in whatever the codes were that gay men used to flag each other, to attract each other. Cops were doing it intentionally to attract them and arrest them.”

Lawrence vs. Texas was a landmark Supreme Court case in 2003 that officially helped put an end to the criminalization of sodomy. The court ruled that Texas should not interfere with the private sexual decisions between consenting adults and that criminal punishment for sodomy was unconstitutional across the U.S.

“Gay sex was still illegal in, like, 15 States until 2003,” Manion said. “That was the justification for so much blackmailing and harassment of gay people and trans people by the police because they could still charge you with sodomy and you would actually go to jail for having consensual sex with another adult.”

Cross-dressing laws, which are believed to have first appeared in Columbus, Ohio in 1848, also encouraged officers to harass and abuse trans or queer people for dressing in clothes that didn’t correspond with their biological sex, Manion said.

Officers sexually assaulted and harassed arrestees, forcing underwear checks on people they suspected of cross-dressing, according to Manion.

“Being a feminine man or masculine woman was a signal that you might be gay,” Manion said. “That's why the cross-dressing laws were such a kind of frontline, easy way to really police and harass everyone whether they were queer or trans.”

Fight continues

The fight against discriminatory laws continues to this day.

New York’s section 240.37 in the state penal Code, which was also known as “walking while trans” law, was enforced until Gov. Andrew Cuomo answered calls to end the measure in February.

The New York policy from 1976 vaguely aimed to prevent sex work, and allowed for the arrests of people who were suspected of prostitution. But the oversexualization of transgender people led to the disproportionate arrests and harassment of trans people in public spaces for walking, standing and just being in a public space. It wasn’t repealed until this year.

Cuomo signed legislation to repeal the measure, saying it “is a critical step toward reforming our policing system and reducing the harassment and criminalization transgender people face simply for being themselves.” Mayor Bill de Blasio has also put forth reform to decriminalize sex work, and offer community-centered services for sex workers.

Still to this day, research shows that the LGBTQ community is affected by policing and incarceration than their heteronormative and heterosexual counterparts. According to the Prison Policy Initiative (PPI), a criminal justice research and advocacy group, LGBTQ people, of every age group, are overrepresented in the criminal justice system.

In 2019, a PPI study found that gay, lesbian, and bisexual individuals were 2.25 times as likely to be arrested than straight people. The disparity is heightened when the research is narrowed down to lesbian and bisexual individuals, who are 4 times as likely to be arrested than straight women.

Across the board, PPI’s research shows that LGBTQ people of color are disproportionately harassed and incarcerated by police. Historians say these disparities are long-standing and are part of the ongoing movement for gay rights.

“The relationship between the LGBTQ community police departments across the United States is, in a word, complicated, partly because of that history of brutality against LGBTQ people, but also because of the recognition that the LGBTQ community is not a monolith,” Beswick said. “We have members of our community that continue to be brutalized -- are afraid of police -- just on the basis of the number of killings that have happened of black and brown folks, black and brown trans folks.”